THE HUMAN STATUES OF MANDALAY

FEATURE Nº10

Hundreds of men, women and children covered in white dust occupy a small lane in Mandalay each day.

By Fraser Morton

& Eszter Papp

If you catch them sleeping they look like stone, until their eyes blink open and the Kyauk Sit Tan carvers go back to work.

In a city that throbs with artisans who are experts in gold-leafing, woodwork and textiles, one little lane in Mandalay, the former royal capital of Myanmar, is filled with Burmese men, women and children who are renowned for their skill in sculpting.

The carvers of Kyauk Sit Tan have been here since the 18th century, with generation after generation learning to carve, sand and polish marble and stone into the figure of Buddha.

Few masks are worn by the carvers on Kyauk Sit Tan.

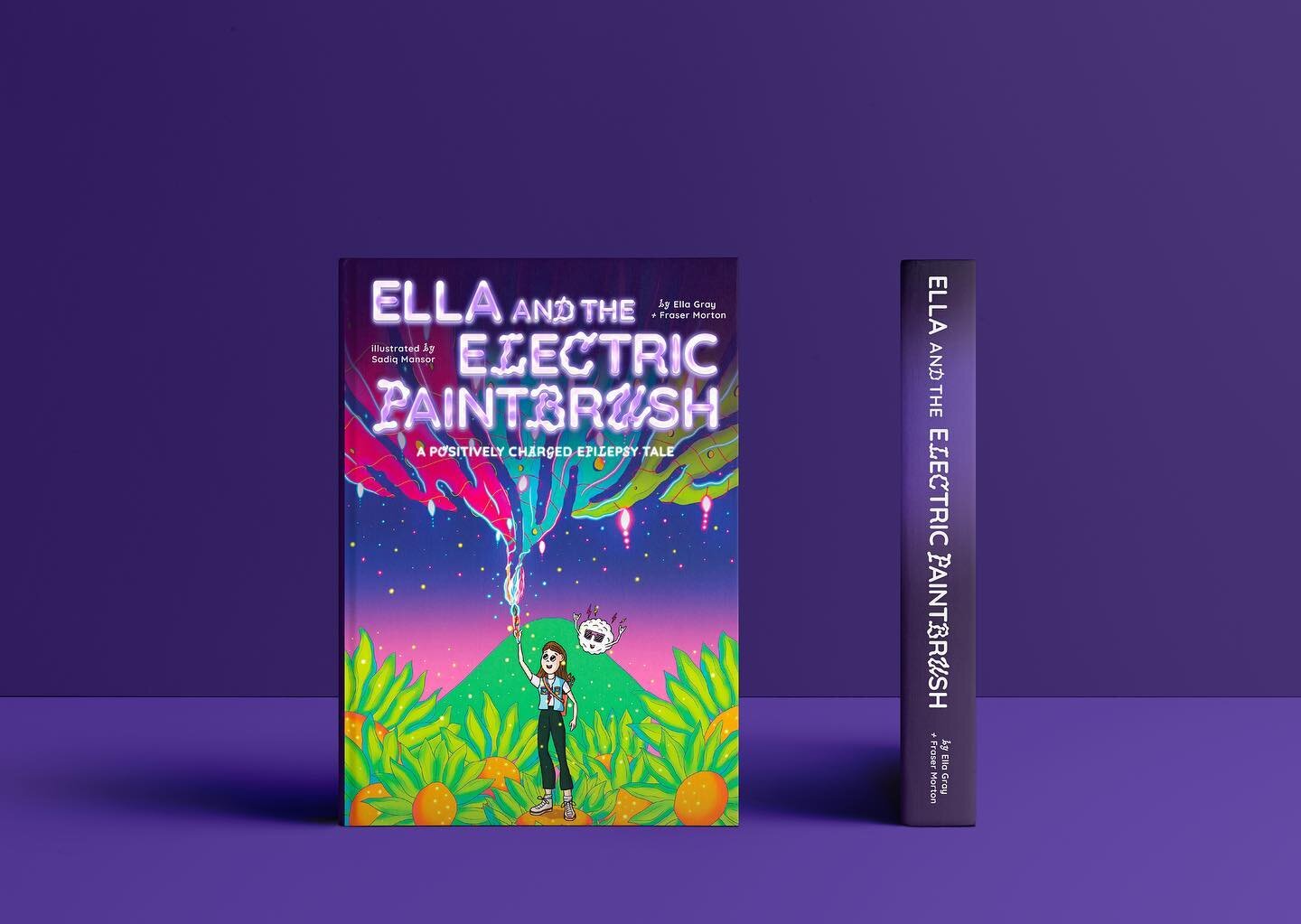

The Buddha statues made here are shipped across Asia, Europe, the United States and beyond for religious and decorative purposes.

Yin Yin Htwe says she has never thought of doing anything else. "Stone carving is a business handed down to me by my ancestors," she says. "I have been doing this job now for 40 years. I hope to pass on my business to my children too."

Finished Buddha statues, highly soughtafter and shipped worldwide.

A young carver takes a rest in the shade from the searing midday heat.

"I gain merit as a Buddhist, but this is also my business. Having this business makes me feel delighted, and I want to say ‘Well done’ to my customers for showing their faith and respect for religion."

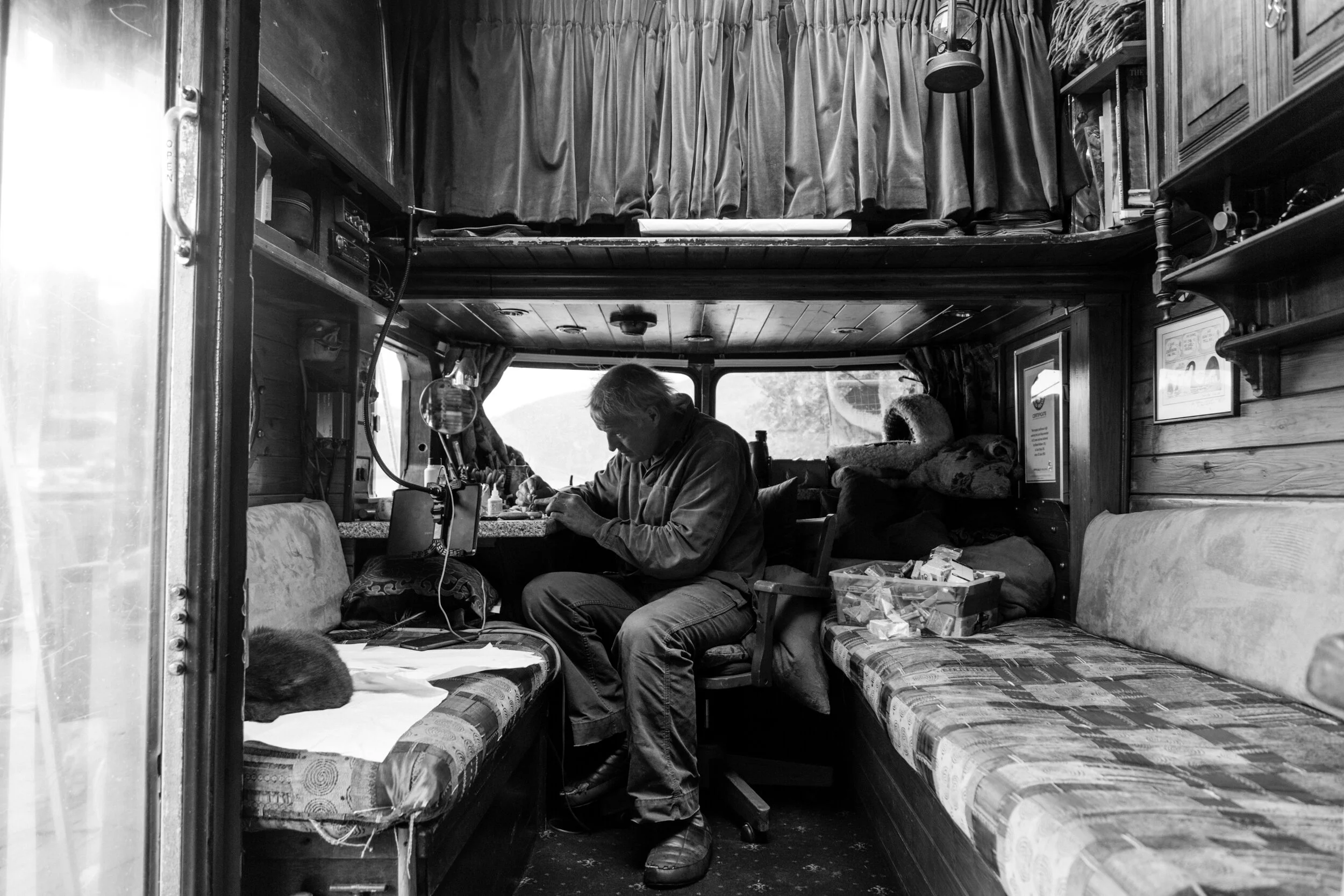

Many of the workshops here have been handed down four generations. At most workshops the entire family pitches in: The men hammer and lift heavy stone while women and children add intricate detail. Everywhere there is dust. It clings to hair, eyelashes, nostrils, hands, shops and cars and hangs low in the tropical heat. It’s a compelling scene that is drawing travellers. They come to see the carvers and their craft, which has been set in stone for centuries here in a little lane in Mandalay.

Today, power tools have replaced crude carving instruments.

Teenage stone carver.

Portrait of a carver.

Thousands of statues line the lane.

One of hundreds of stone carvers on Kyauk Sit Tan.

Some statues arrive at Kyauk Sit Tan with only heads to be finished by the skilled carvers along this little lane.