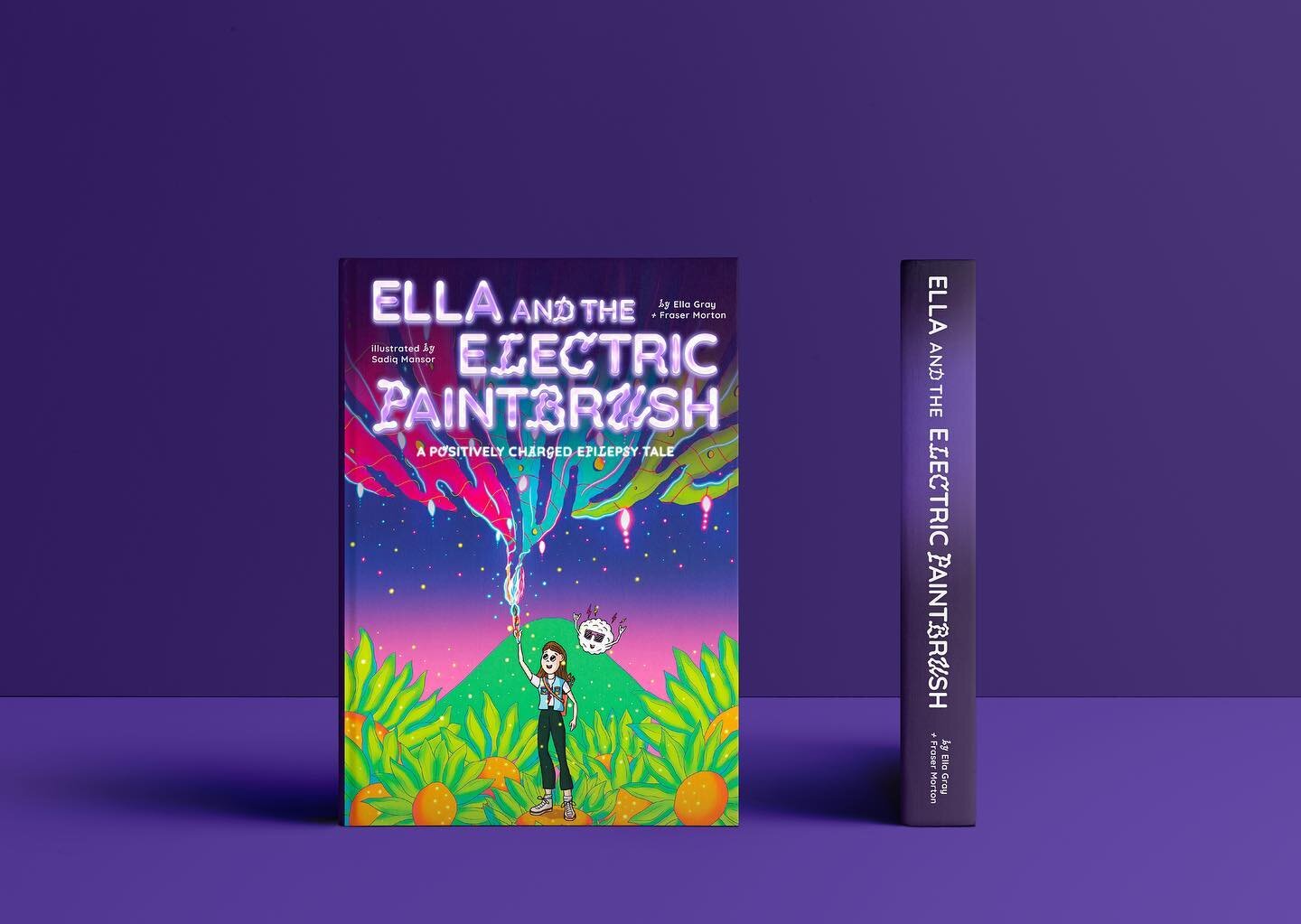

LONGNECKS OF LOIKAW

FEATURE Nº12

A NEW TOURISM CHAPTER FOR THE LADIES OF LOIKAW

By Fraser Morton

Photography by Eszter Papp

It's a mystery why the women in Loikaw began wearing gold rings around their necks, even among the tribe themselves.

One story claims the rings stopped tigers from dragging women away by the neck. Another tale goes that it was to lure men from other tribes, and yet another suggests it was simply a fashion fad that caught on.

Whatever the origin, the longneck ladies of Loikaw are renowned throughout the troubled Kayah state of Myanmar, and they are the reason for a spike in travellers heading here in recent years.

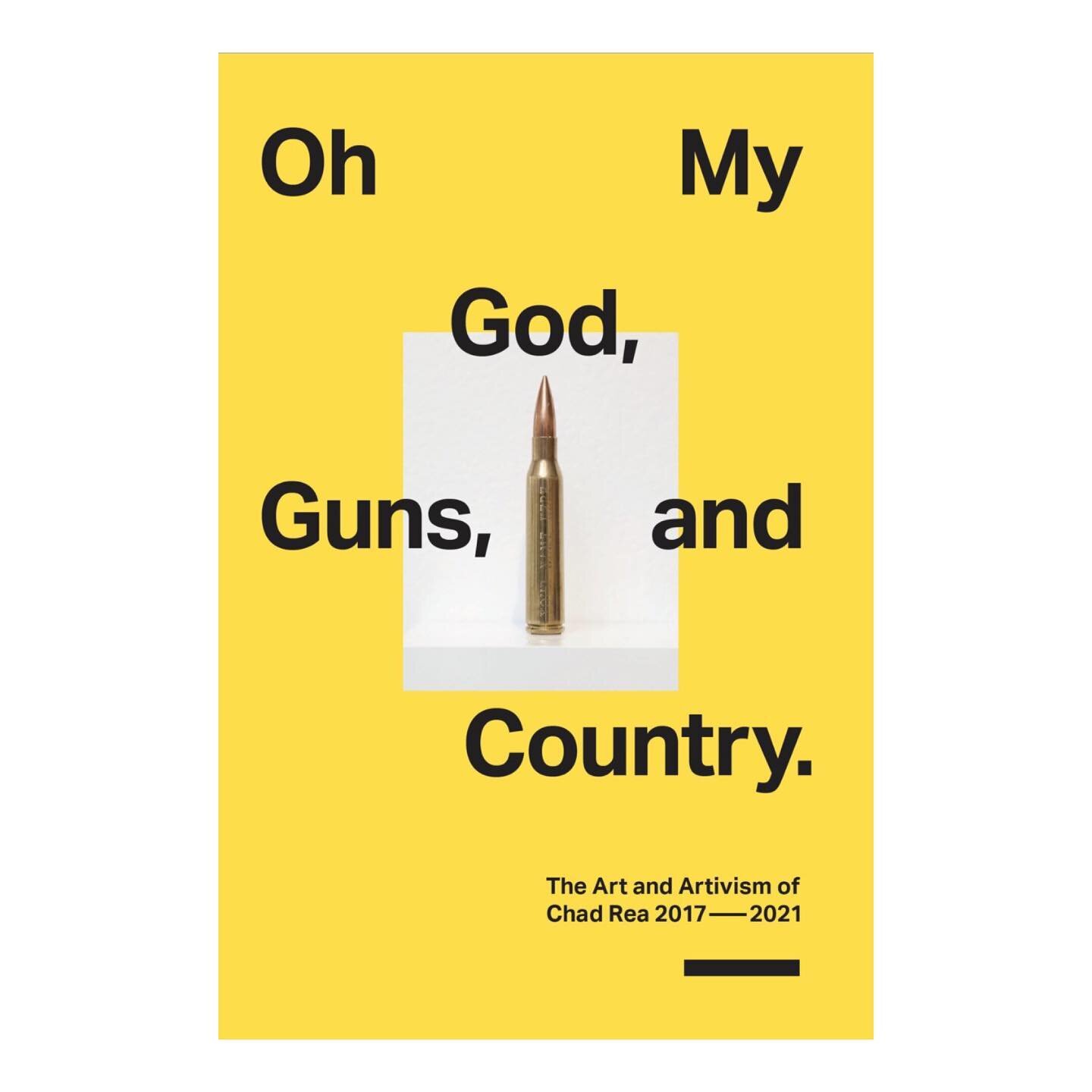

Handmade Loikaw cotton scarves.

Cotton farming was the main income for the ladies before tourism.

From the 1950s until 2013 the state was a war zone between the military and armed ethnic groups that displaced thousands of refugees to Thailand and was locked off to the outside world.

However, since the country's first democratic elections in 25 years took place in 2015, this long-time off-limits - and one of the poorest regions of the country - is building a future chapter of prosperity, with new guesthouses, restaurants, infrastructure and jobs being created to meet the tourism demand.

The new face of tourism comes with challenges for the longnecks ladies, too. There’s already fierce debate among the traveller community about the villages being turned into “human zoos”. A claim based on the assumption that the tribal traditions are being transmuted to cater to the tourism intrigue.

There has been efforts to build a sustainable tourism model, and in 2014 an initiative was launched by the United Nations World Tourism Organisation to create jobs for the local communities and rebuild ethnic villages following decades of obscurity. An award-winning film was also made to promote the region, which you can watch here

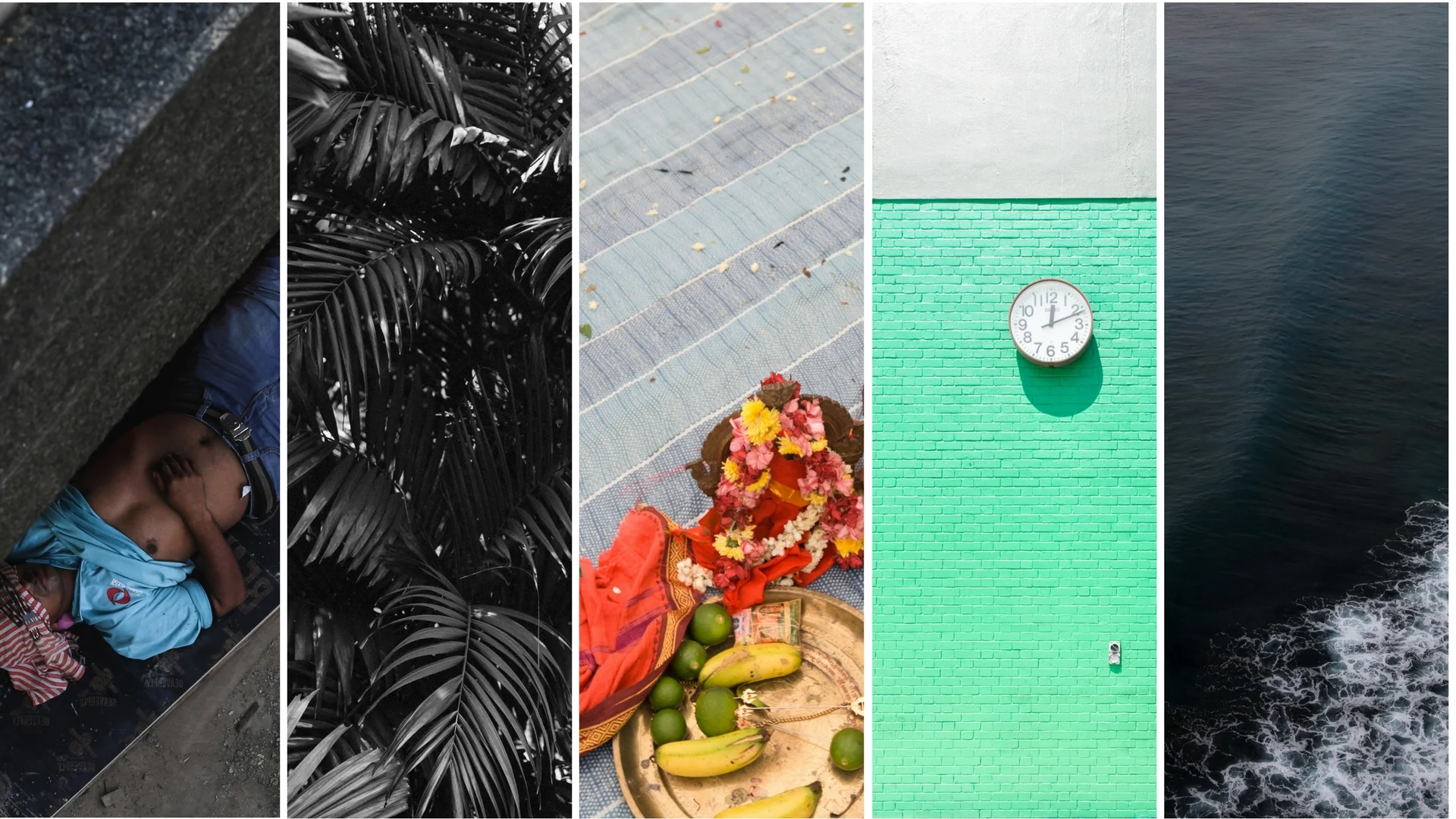

Mu Aye on the stoop of her home.

In the kitchen of her home she shares with 6 relatives.

We spent an afternoon in Pan Pet visiting the longneck ladies - who also don’t mind being called this contrary to popular belief - and what we found was far from a human zoo. We found people proud to share their customs with strangers.

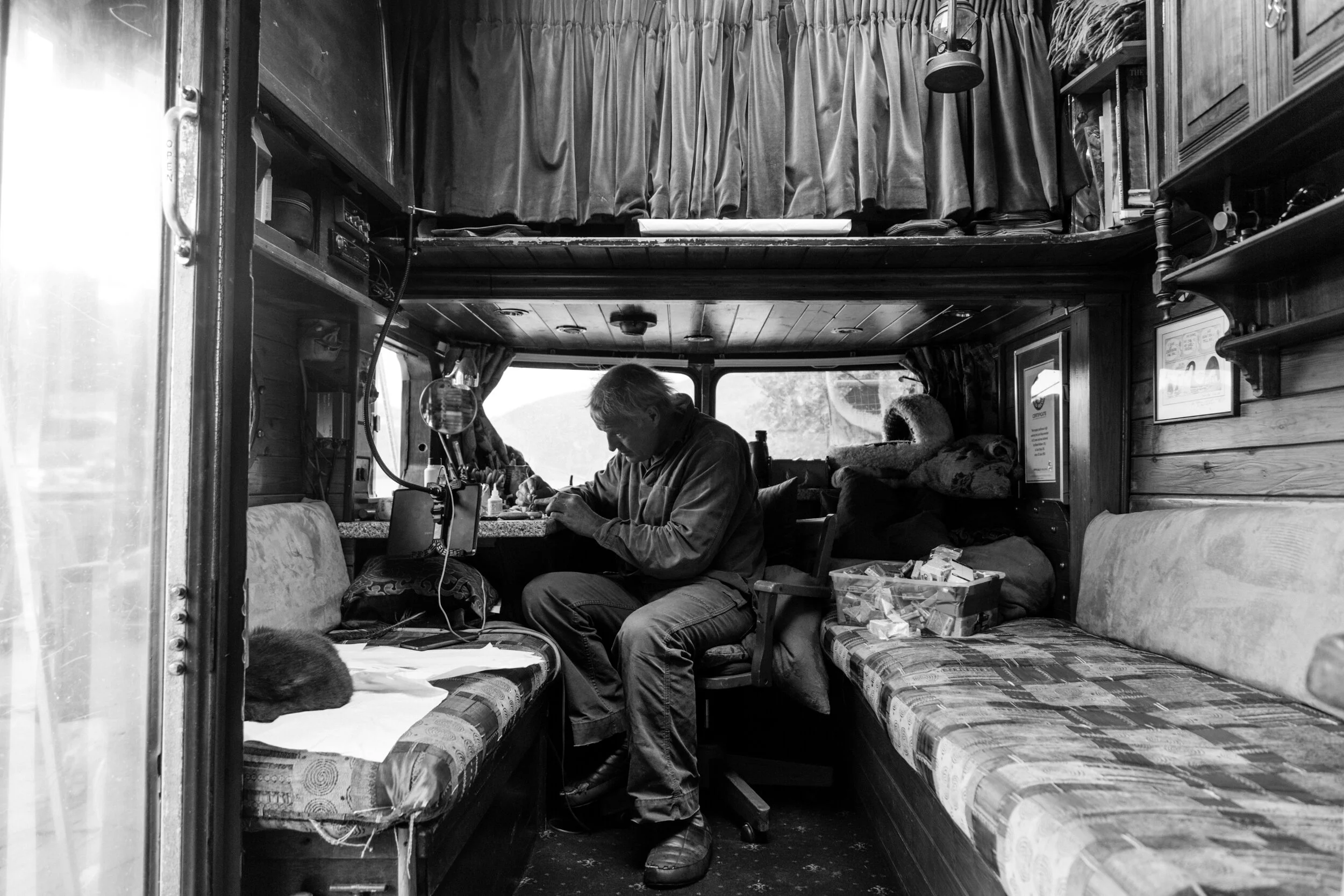

It’s a still place. There’s hardly any sound. A light whistle of the wind and the occasional groan from a meandering cow, but other than that there’s silence.

Located along a bumpy dirt track about an hour’s drive into the hills from the state capital Loikaw, today Pan Pet is undefiled by tourism. There’s a market on the edge of the village where we saw a road-beaten traveller buying a scarf from a longneck lady. Entering the village is unremarkable and consists of a collection of about 20 stilted huts surrounded on both sides by sparse, parched cotton-fields. Everywhere there is red dust. The heat is searing. Homes have no doors or windows, a simple wood fire in a large room and two small rooms with a mat on the floor to sleep. The stoop is the communal area and where the ladies sew and hammer their rings.

The longneck ladies live in their huts with their families and extended relatives and spent most of their days sewing scarves and garments that they wear and also sell to visiting travellers.

Rice wine.

She sometimes drinks a pot a day.

We sat on the stoop of Mu Aye’s home for a few hours, chatting and sharing a pot of pungent rice wine. Her neck and legs were bound with rings and she wore full traditional wear of her tribe.

She told us she has been wearing the rings since she was six years old. She didn’t know the origins of the tradition, and she told us the tiger story, the fashion story and the love story. She said they all could be true.

She told us that before 2013 her and the other women relied solely on making money from cotton farming, about US$20 per month. Today, each tourist - of which she gets about 10 per month - pay US$2 to visit her homestay and she makes extra money selling her handmade scarves. We bought three for US$15. She says she would much rather be making her garments than farming.

“We plant cotton in the fields. We harvest cotton in the cold season, and my hands hurt with the freezing cold,” she said.

“There’s also no water when we are working in the fields. I prefer to stay with my children and make garments.”

Mu Aye previously worked at a handicraft tourist shop at Inle Lake, where she sat for hours in her traditional dress to gain the attention of passing tourists to pose for photos in exchange for money. A job she didn’t like because she missed her family. So the issue of exploiting these women tradition purely for tourism is present, but she says this is not the case in Pan Pet.

Mu Aye says she is unsure if children will continue to wear the rings.

"Not many girls wear them now. Some do, but not as many today as when I was young, but I do hope our tradition will live on."

Before we leave we ask Mu Aye if she has any hopes for the future?

"I’ve always wanted to see Yangon," she said.