SECRETS OF THE SIKEREI

FEATURE Nº13

A JOURNEY TO MEET THE SIKEREI SHAMANS, WHOSE SECRET LIVES IN THE JUNGLE ARE UNDER THREAT BY MODERNISATION.

There's no distinction between daily life and the divine on Siberut Island, the largest island in the Mentawais and where we have travelled 60 kilometres upriver to meet animist jungle-dwelling shamans.

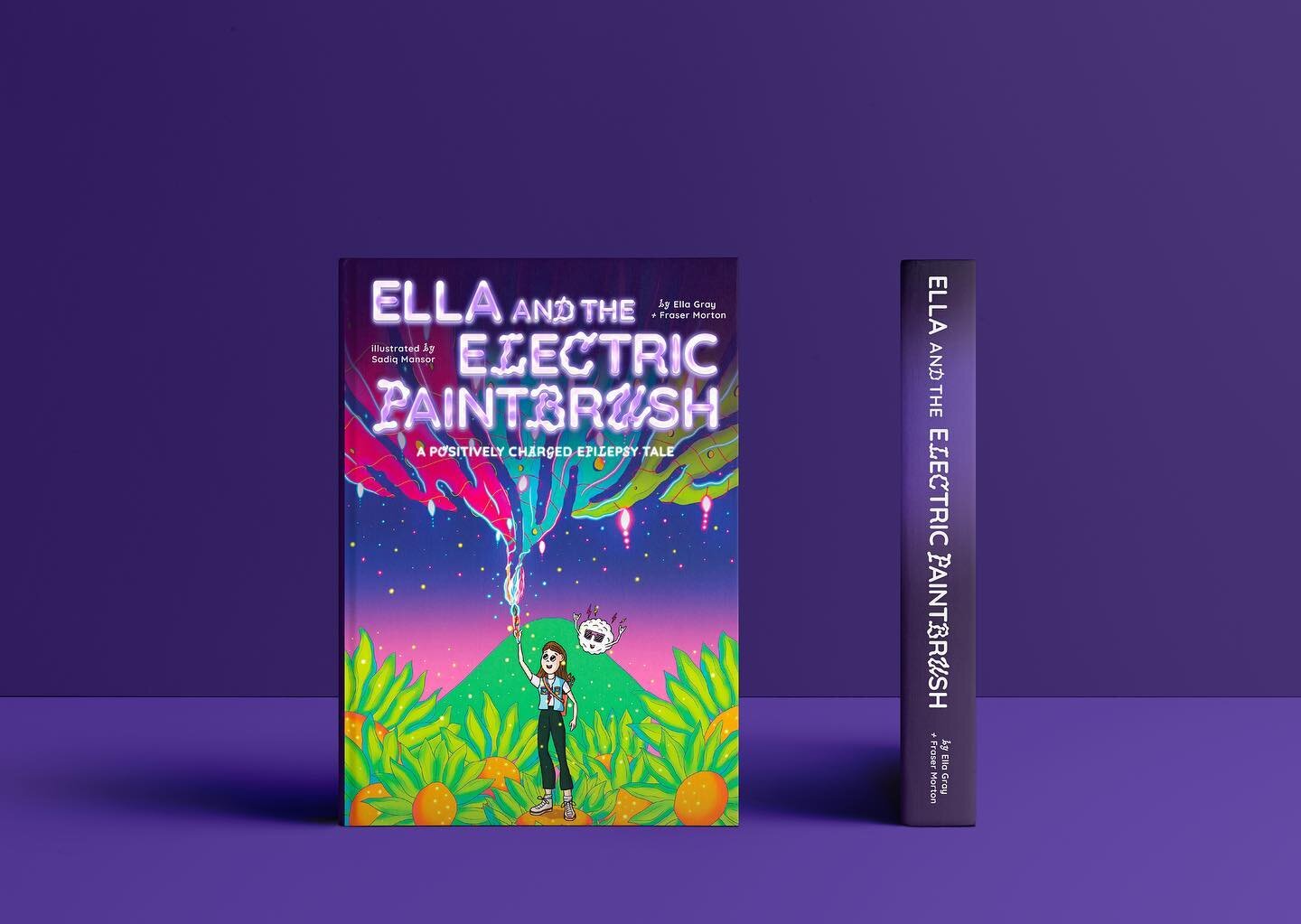

The half-naked tribesman hacks down a sago palm tree, fishes out a massive worm, squeezes it dead and stuffs it into his mouth. His name is Kapik Sibajak, and he is a Sikerei medicine man of the indigenous Mentawai Tribe, and our host for the next few days.

Kapik Sikalabai and her sister about to begin a day's fishing.

The night view from Kapik's longhouse, known as an uma.

The Sikerei are a special class of male forest shamans and healers. They practice animism, wear hibiscus flowers, ink themselves with magic tattoos and sharpen their teeth. They have resisted evangelism, modernisation and government attempts to get them to both resettle and abandon their non-sanctioned beliefs. They have endured and, thanks in part to a trickle of tourism, now are largely left alone to live how they please in the jungle.

Earlier that day we had traveled for two hours upriver with our guide and translator Yen, a relative of the tribespeople, from his home village Muara to our rendezvous with Kapik. He appeared from nowhere from behind a tree in dense jungle wearing only a loincloth, bow and arrow, machete clasped in hand. Kapik loves that machete. It never leaves his side. He’s 69 years old and a prankster. He danced around us as we arduously trudged through knee-deep mud, waded through rivers, tightrope-walked log bridges, and picked and fought our way through the jungle in a race against darkness. He would disappear only to emerge a moment later, bursting into song, shaking his hips and motioning seductively to Eszter. I liked him immediately.

Hunting for sago worms.

Sago worm.

Making clothes.

Kapik is incredibly hard working, despite his age. Daily chores include tending his pigs and chickens that live under his longhouse, known as an uma, hacking down sago trees, fishing, and foraging. He smokes constantly. They have few pleasures here in the jungle and are heavily addicted to nicotine and sugar—gifts that you must come bearing in order to be granted shelter. Our host family— Kapik and his wife, Kapik Sikalabai, along with their middle-aged son Petrus Sekaliou, his wife and their two children, who came from their own home to meet us—is mischievous, loud, flirtatious and hard, but also affectionately hospitable. Kapik is a keen kisser. Both Eszter and I received frequent kisses on the cheek from him.

Kapik Sibajak, Sikerei medicine man.

Over a dinner of plain rice and noodles, Yen intermediates our chat about life. I’m keen to learn everything I can, but also for them to know a little about us, too. Kapik’s four sons are all married and living nearby—but on the outskirts of the forest, where they eschew tattoos and now wear western clothes. I tell them I’m from Scotland and that we too have tribes, called clans, and tribalwear. He’s amused. I show them a photo of a Highlands cow I keep on my phone, and I think Kapik Sikalabai looks impressed. I ask Yen, “Have they ever seen a horse?” When they say no, I pull up a photo of horses I took in the caldera of Bromo Volcano. “Java horses,” I say.

Kapik Sikalabai asks Yen where it is, he tells her Indonesia, and she looks surprised.

Making bamboo mats.

Kapik tending to his pigs.

Making clothes from trees.

Later that night, Eszter and I duck outside the hut for some air and are sucked into a night sky alive with stars, which swallows the jungle, our small hut and both of us in a mesmerizing star-spangled indigo blanket. On the stoop of that shack far from home, amid the snorts and smells of pigs, we stare skyward in wonder until we both laugh out loud.

Poison darts.

I shouldn’t be surprised when that dreamlike serenity is shattered at 3:37 a.m. We are asleep on the wood floor of Kapik’s uma when the screaming starts. It’s the pigs. In the pale moonlight that slices through the open-air hut I see the naked figure of Kapik carrying his machete and striding into the darkness. A second later there’s a sickening clang of metal, a dull thud and what sounds like splintering bone. I really hope it’s not the pigs.

Kapik's sister fishing for river shrimp.

Kapik Sikalabai

River shrimp.

I slip under the mosquito net, flick on my torch and head towards the light coming from the back of the hut. I hear laughter and another clang of a machete followed by a thud, more splinters and a nasty squelching sound. I see them now huddled around a flame torch, all six of the family. Kapik swings his machete and brings it down fiercely onto a log, which splits in two. He pries the glistening pieces apart with the tip of his machete. The logs are writhing and moving on the surface: worms. Hundreds of them. Long, thin, squirming worms ooze from the logs and everyone snatches them up and stuffs them into their mouths. Fat, tree-eating worms, they think, make for a sweet-tasting midnight snack. Kapik spots me, turns machete in- hand, laughs and shoves a worm in my direction. I hate it when this happens on travel assignments. It means I have to eat it. I can still feel the wriggling in my belly as I write this.