#3 — WILL TO WALK: A 33-YEAR ANTARCTIC ODYSSEY

In this episode, polar activist Sir Robert Swan gives an exclusive interview about his recent Last 300 expedition to the South Pole. Hear what happened on his historic walk in what was meant to be the culmination of a 33-year odyssey to cross the entire Antarctic continent on foot.

Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please post a 5* rating on Apple Podcasts or at ratethispodcast.com/twopoles.

Follow @two_poles @farfeatures & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

WILL TO WALK

THE FULL STORY OF A 33-YEAR ANTARCTIC ODYSSEY

By Fraser Morton

In front of him lay the first step of a 300-mile journey on foot across the barren ice desert of Antarctica. Behind him the history of his polar achievements played on his thoughts.

A final walk to the South Pole. His Last 300 Expedition, a fitting name for the final chapter of a 33-year trans-Antarctic landmass crossing on foot.

“Not for records, not for anyone. This one's for me. Do what you say you are going to do,” the explorer heard his own mantra.

He peered into the white abyss and felt familiar awe and dread. Not easy to describe, but inescapable in his dreams. A pull, like a magnet, sliced through the empty landscape and stabbed into him.

“I shouldn’t even be here,” he thought.

The distant call of the wild places had started in his childhood and echoed through his life as an ever-present tug at his insides. It had hardened his body, moulded his will and pushed him further than he could have imagined. The first person to walk to the South Pole (1986) and North Pole (1989). The Polar Medal. An Officer of the British Empire. A United Nations Ambassadorship for Youth. Author, speaker and mentor to thousands of environmental activists around the world. But mainly, he was a survivor of the polar places, and all because of the landscape’s silent call.

The boy had grown to become a man of achievements because of his will to face the ice frontiers. And now, as he stood with his feet in boots, clipped in skies, wrapped head-to-toe in layers of survival clothes, he peered out through masked vision upon a landscape where he would face a final test.

The first step of thousands lay ahead. As did the sound of his skis and sticks pounding snow, accompanied by the crunch, swoosh, slap, and grunts of relentless, monotonous marching while dragging his heavy sled. Exhaustion, disorientation, sleeplessness awaited somewhere out there on the ice. As did soon to be spoken “shits”, “damn its” and “bloody hells” over inevitable, tiny, errors in judgement by a soon-to-be-sleep and-oxygen-deprived-brain. Punishment awaited in frozen fingers, frostbitten toes, chaffed and bloodied thighs and absolute bone-rattling exhaustion for this 63-year-old man. He had planned for all potential pitfalls his imagination could dream up. This time, he felt prepared. His new hip had healed. He had trained for two years. He felt strong. He pushed away thoughts of agony on the ice two years ago.

“Game on,” he thought.

And then came the first step on December 2, 2019, Sir Robert Swan began what was to be his last 300-mile march to the South Pole.

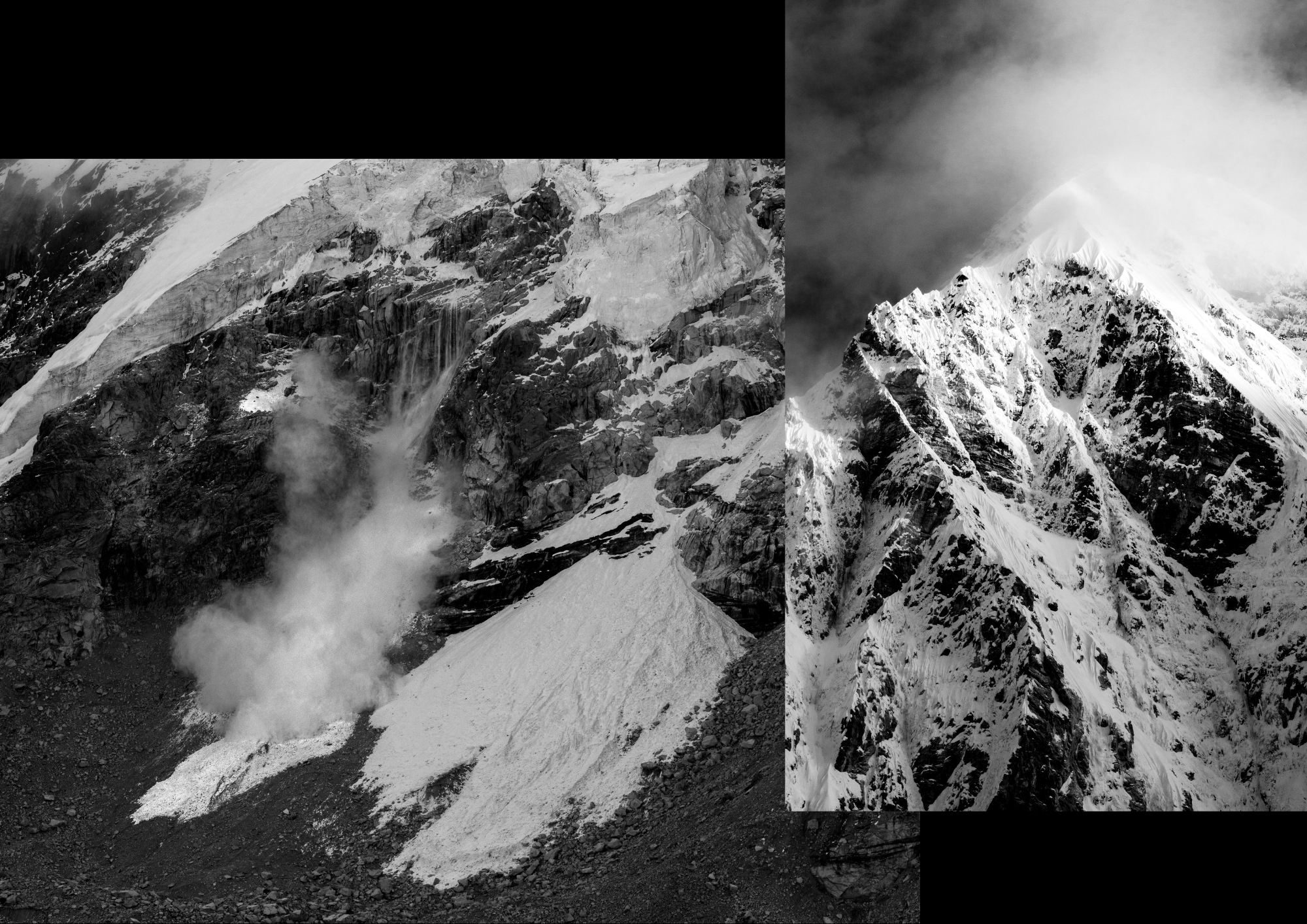

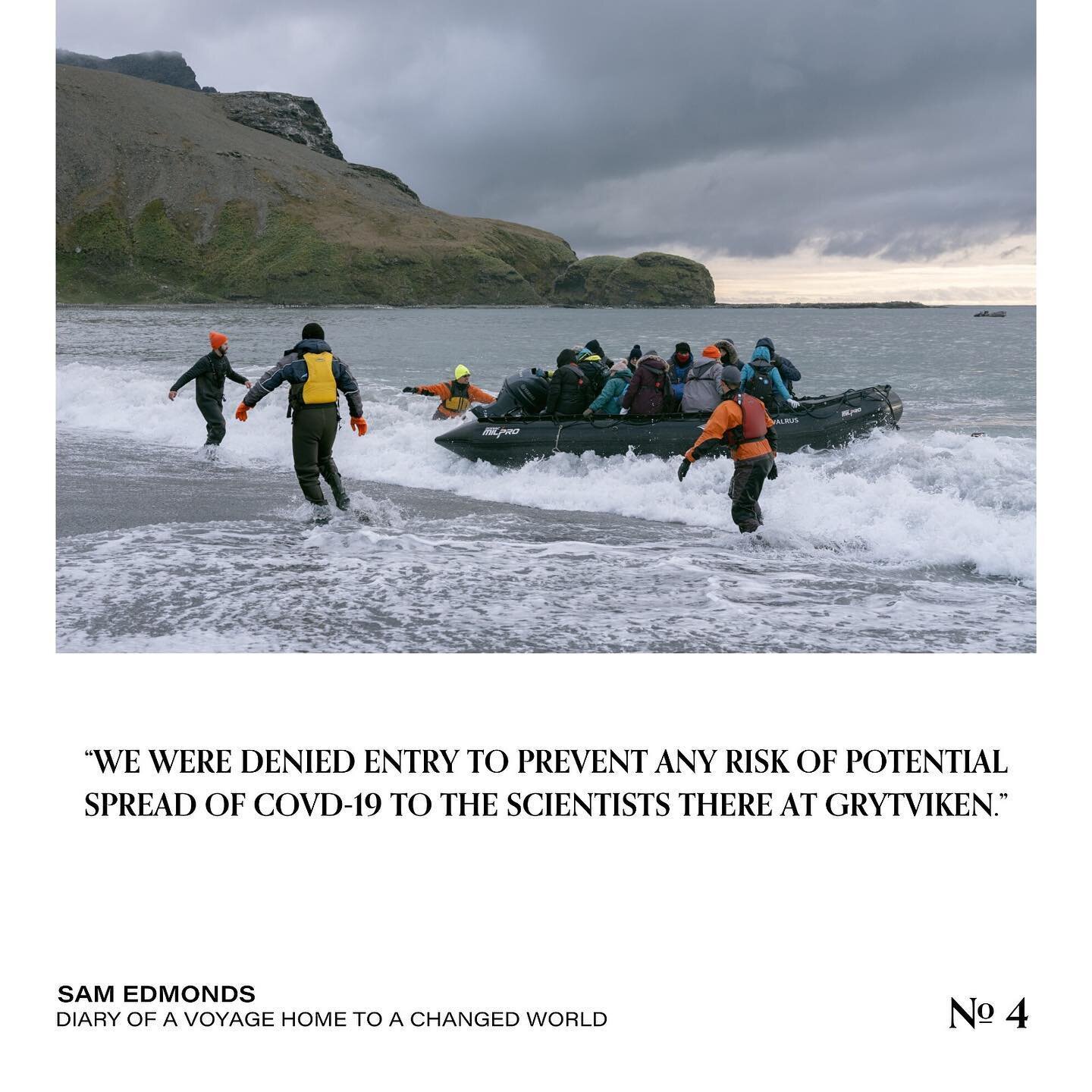

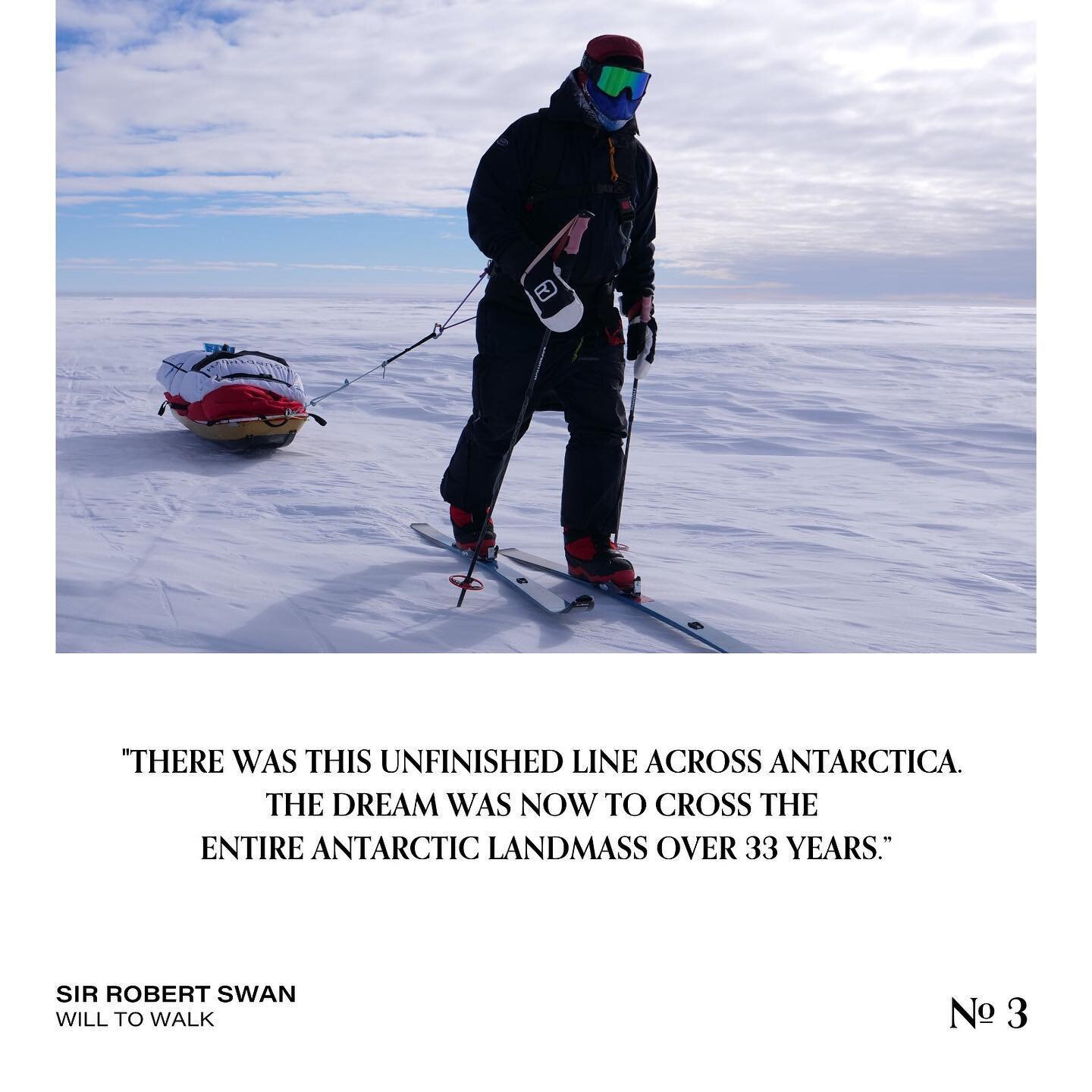

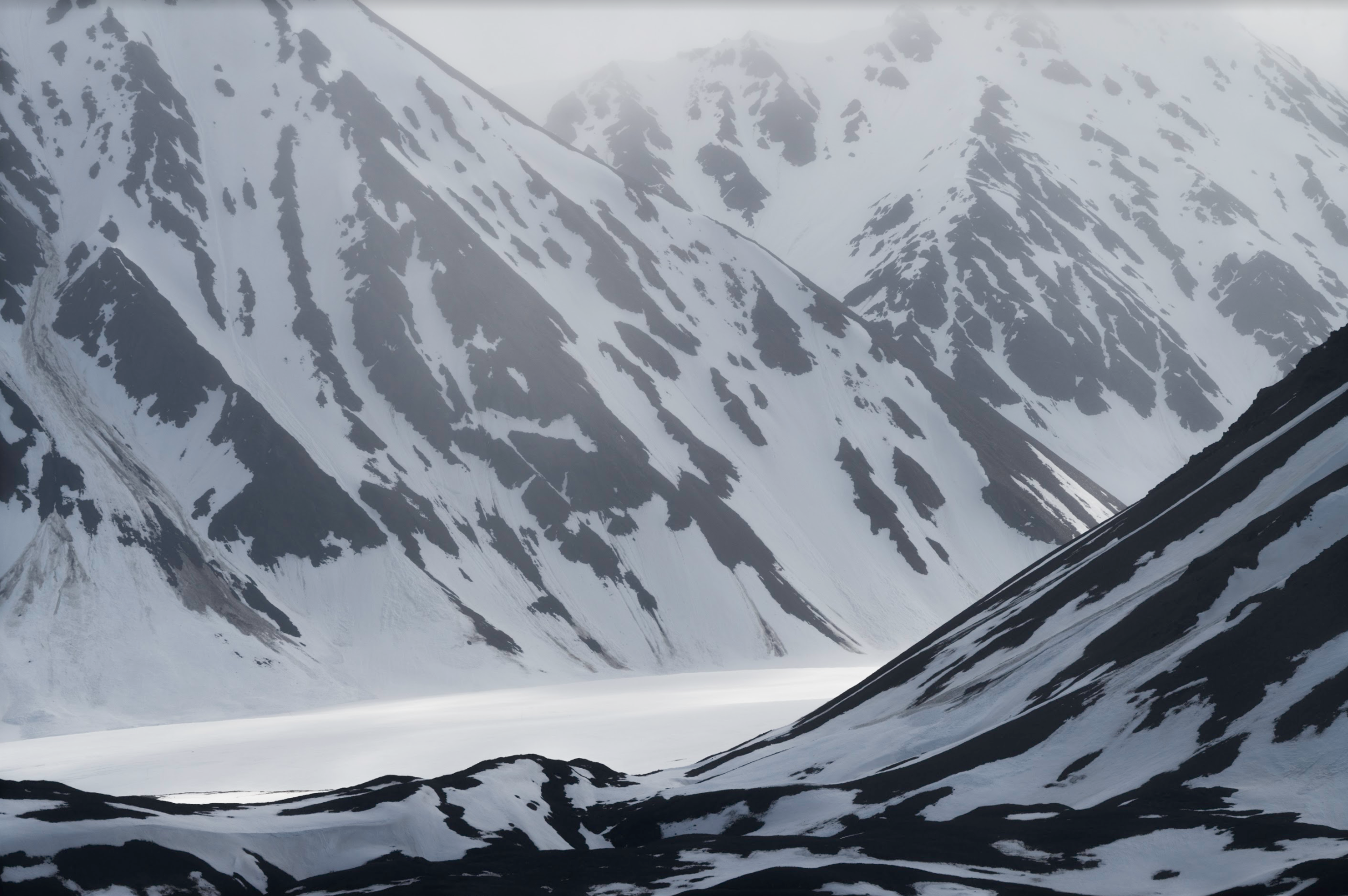

Sir Robert Swan, Last 300 Expedition, Antarctica. Photo: Kyle O'Donoghue/2041 Foundation

OUT OF RETIREMENT 2019

Swan was breaking a promise to himself. This was the second time he had broken polar retirement.

“When I reached the North Pole on May 14th, 1989, I didn’t just hang up my skis. I screwed them to the wall. This was never going to happen again.”

While his 1980s expeditions etched his name in the history books alongside his heroes, the expeditions were plagued by setbacks and extreme conditions, including losing a ship after it was crushed by pack ice on the 1987 South Pole Footsteps of Scott , and almost drowning during his 1989 Icewalk due to unseasonal climactic ice melt in the Arctic Ocean.

Even taking these near misses into account, he still believes that on those occasions the landscapes “allowed him to pass”.

“Antarctica let us through and I sort of didn't really understand that at the time. Of course, we lost our ship, we had all kinds of difficulties, but Antarctica did let us through and for the North Pole, the ice cap melted months before it ever had, but again, we were let through. You can never win over these places. I was 100 per cent totally convinced that I would never do a big polar journey again.”

But 28 years later, Swan’s 24-year-old son Barney convinced his father to join him on an expedition to the pole called The South Pole Energy Challenge. The idea came after the pair visited a NASA facility and were shown a map of Antarctica highlighting the imminent threat of a break up of the massive Antarctic Larsen C ice shelf due to climate change.

“NASA was saying, no one is listening to us. We need to get people taking this seriously.”

Soon after, the younger Swan founded the Climate Force Challenge, a seven-year mission to clean up 326 million tonnes of Co2 by the year 2025 by championing clean energy use and working on clean-up missions worldwide.

To Launch Climate Force, father and son would undertake The South Pole Energy Challenge (SPEC).

And so shortly after celebrating his 61st birthday, Swan pencilled in December 2017 as the SPEC starting date – 30 years after his first successful South Pole expedition.

“The dreams of the 11-year-old in me were reborn. I felt like there was this unfinished line across Antarctica. The dream was now to cross the entire Antarctic landmass over 33 years.”

Last 300 Expedition, Antarctica. Photo: Kyle O'Donoghue/2041 Foundation

600 MILES TO GO

In December 2017, Swan senior and Barney set out in a team of four on a 600-mile march that would become the world’s first renewable-energy powered expedition to the South Pole. A feat never attempted on the North Pole, either.

NASA ice melters powered by the sun adorned their sleds, biofuels boiled their meals, and daily audio and visual broadcasts were beamed back to the world with live messages for their following fans.

They hauled sleds that weighed over 100 kilograms. As the march wore on, every muscle in Swan’s then 61-year-old body began to ache. His harness cut and chaffed, leading to bloodied skin. Frostbite set in. Gripping his ski sticks numbed his frozen hands. Barney’s toes began to rot. And what started as discomfort in Swan’s hip fast developed into long days of agony and sleepless nights under the midnight sun.

It had been thirty years to the month since he had walked to the pole, but looking around, the place hadn’t changed a bit. It was a timeless empty landscape. The only thing in sight to have aged, was him. The game had changed.

As the 2017 march wore on, Swan began to fall further behind each day. His heavy sled cut deeper into his hips. His arms ached from pounding his sticks into the snow. Everything ached and felt heavy. His mind kept racing back and forth between 1987 and 2017, step by step, decade by decade, the lines of time began to blur.

“If I had got slow 30 years ago on The Footsteps of Scott expedition, I wouldn't be talking to you now. I'd be dead, because without radio, without backup, if you got slow, you were left to die because the others couldn't help you. There was no way out. There was no communication.” As he marched on, following the ski tracks made by his teammates in front, the space between him, Barney and their other three teammates of Kyle and Martin grew further apart until they were tiny red dots on the white horizon ahead of him. He entered the “ice cell”, like some sort of ice mirage.

“When I would fall back from the team, I would see them as little red dots on the horizon. Thirty years ago, everyone wore red, and we still do today.”

Back then, he and his team were the first people to reach the Pole on foot after his heroes Roald Amundsen and Robert Falcon Scott. It had been a tough expedition, “But I had been there, done it,” Swan said.

“The older you get, the more likely you're going to get smacked by Antarctica and taught a lesson. I don't feel like I’m an old person in any way, except when I'm in Antarctica because it looks for weaknesses that you have. You might have weaknesses when you're 30, but you’ve got a hell of a lot more when you’re 60+, so this time Antarctica was looking closely at me and saying, what can we get from him? And this guy’s pretty good…maybe his knees, no, they are all right. And his back is okay, but this here, this looks interesting, maybe we can get him on the hip! It’s like a scuba diver. You go into the water in a wet suit and if it’s not done up properly, you can feel the cold water creeping in, finding something, flooding your senses with that terrible cold.”

On the morning of December 11th, Swan was losing so much time he knew the team would not be able to make their allotted distance to the Pole to stay on schedule. He skied ahead to Barney.

“Can you get there without me? he asked his son, “I can’t go on.”

“Yes, I can,” he replied.

They were 31 miles away from the midway point of their 600-mile march.

“It was the first time Antarctica really gave me a kick in the teeth. It kicked me hard and my hip disintegrated. I couldn't sleep, and the pain was immense.” Later on what was a beautiful windless day, Swan sat on the edge of his sled and watched the propeller airplane land on the snow to make the emergency airlift. Antarctica would not let him pass this time. As Swan made the short flight to the South Pole, Barney and the team continued on, finishing their march on January 15, 2018.

“That was so terrible for me because I was beaten. And it hadn’t happened before. Antarctica had slapped me in the face. It hadn't let me through. You have to realise in my head I was back 30 years before. Been there, done it – 300 miles for me wasn’t far.”

While the expedition was deemed a team success by showing that even in the harshest environment on Earth it’s possible to survive on renewable energy technology, Swan had the hard truth of accepting his own limitations.

In early 2018, he underwent a hip replacement surgery in the United Kingdom and returned to his home in California to recuperate for a few weeks before returning to Antarctica – yet again – with Barney to lead a Climate Force expedition through his 2041 Foundation with more than 100 young climate activists from 29 nations. Upon return to the USA, he felt invigorated from the voyage, and began planning another retirement vacation back to the South Pole. In big bold letters he wrote “Last 300” in December 2019 in his calendar.

With his new hip, he began his training regime: Practising yoga, dragging tyres up and down the hills in Santa Cruz, cycling over 150 miles a week as well as altitude training. During his rehabilitation, Swan drew inspiration watching tennis player Andy Murray, who had undergone hip surgery and made a dramatic comeback.

“I thought if he can pound up and down the tennis court, I can do this. If you are the first person to walk to both poles, you have the confidence to say, “I can do this again”.

OUT OF RETIREMENT — AGAIN

2019

By early 2019, Swan had assembled a team and preparations for the Last 300 expedition were gathering pace. He enlisted Swede Johanna Davidsson, a record-holder as the fastest woman to ski from the coast of Antarctica to the pole unsupported, as well as Norwegian cross-country skier, guide Kathinka Gyllenhammar and South African-Norwegian filmmaker Kyle O’Donoghue, who had marched with Barney to the South Pole on SPEC two years earlier.

Swan continued to give lectures throughout the year, travelling to 27 Nations to give motivational talks about survival, leadership and sustainability at conferences, schools, universities as he had done for the past 30 years. Every ton of carbon he produced was cleaned up by Barney’s Climate Force mission. All the while, plans for his next polar walk ticked along behind the scenes.

“While Antarctica was saying, it’s time to step back Rob, it was very hard to have been beaten after I had said to everybody that I was going to complete this journey. I ask lots of people to take small steps towards sustainability and our survival on the planet. I said I was going to do this and I’m bloody going to finish the crossing of the Antarctic landmass.”

Months of gruelling training followed. More ropes, harnesses, tyres, heat, sweat, and odd looks from morning runners as the 63-year-old dragged make-shift sleds up and down dusty Californian hill trails. His new hip grew stronger.

“Game on.”

In summer 2019, Swan voyaged to the Arctic on another of his 2041 Foundation missions aboard the National Geographic Explorer with Barney and a group of scientists, journalists, sustainability business people and youth climate activists. Little did he know, his climate change educational tour would sail through the hottest-ever summer the Arctic had experienced.

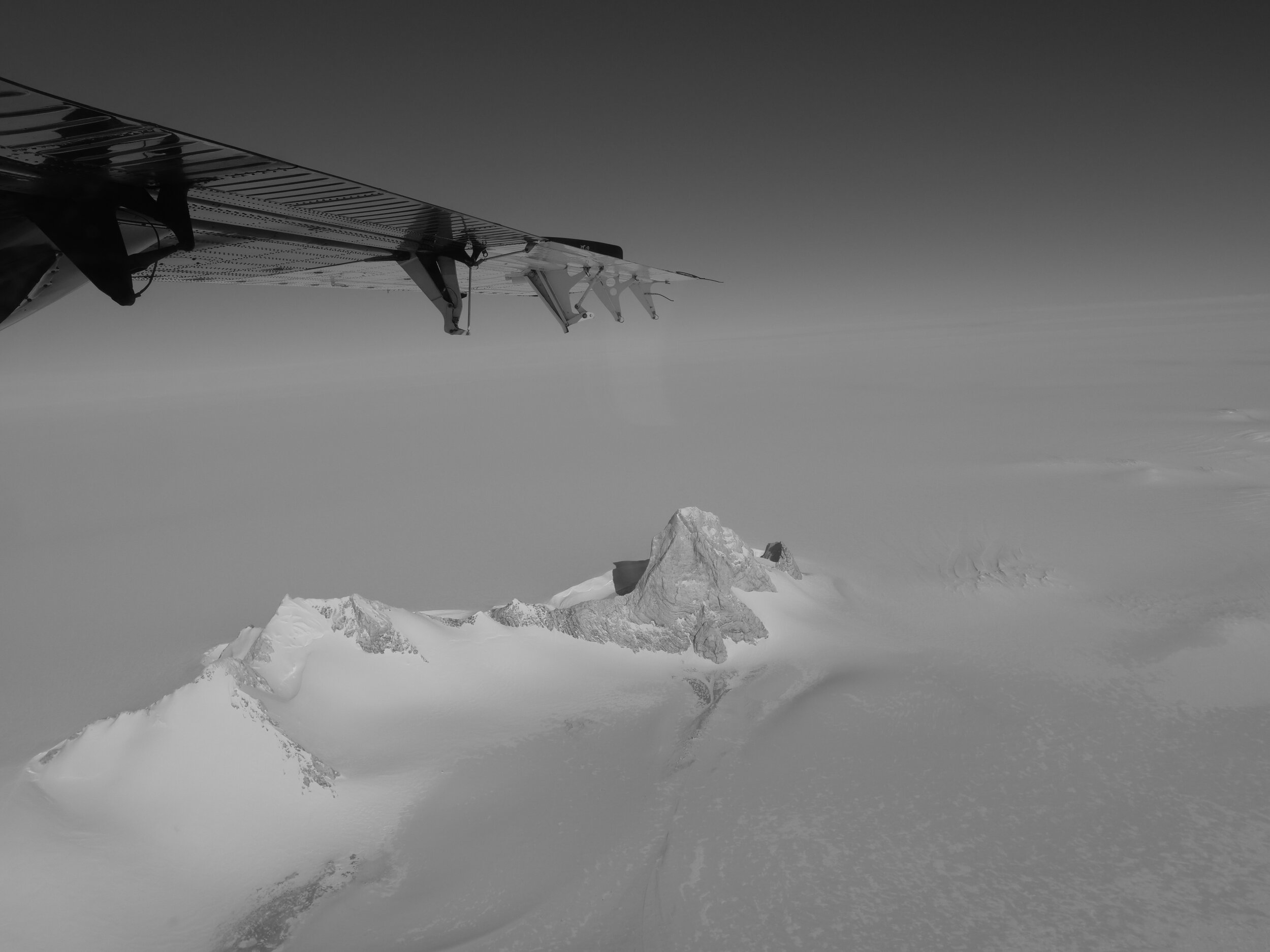

On December 2, 2019 Swan and the team boarded a prop plane at the Union Glacier base camp run by Antarctic Logistics Expeditions (ALE), they flew over the vast icescape and the route Swan had previously walked and landed at the “exact same patch of snow” where he had been airlifted out two years earlier.

The team was 300 miles out from the pole. Swan sent a short message via sat phone, which beamed their location to the GPS tracker on the 2041 Foundation website, “Landed, the journey begins!”.

His training had paid off. His hip had healed. His doctors were happy. And he felt physically and mentally ready.

“Game on.”

“I went into the Last 300 with a new attitude,” he recalled.

“I knew that I’d overcome something very important as a man to not feel embarrassed about asking other people for help. Gone was the macho man. I felt confident that this time I could say to Kathinka, Johanna and Kyle, look, I’m struggling, please take some weight without feeling like a failure. We were a team.”

The team made a steady pace over the first 100 miles amid sweltering conditions for Antarctica.

“It’s almost boring to say with these records being broken on a daily basis – but it was the hottest weather ever at 85º and 86º South. When you think of the temperatures that Scott and Shackleton had at those latitudes of -20ºC, we had -5 ºC. It’s kind of unbelievable. But while the surfaces were a bit strange, we got stuck in.”

All Swan had to do was get to 89º South, 60 miles from the pole, where his son Barney and his Last Degree expedition team of five would be waiting, and then they would all march the last 60 miles in celebration together to the pole.

“I would have completed the crossing of the Antarctic landmass and we would undertake the celebration walk. A great trip all together. That was the plan. Get to 89º South, job done.”

THE LIFE FORCE OF THE ANTARCTIC

Swan speaks of the life force of the continent. About “the lack of compassion”, of “being let through”, or like the ice itself was alive and “looking for your weaknesses”.

To describe the human-environmental relationship while crossing Antarctica’s plains he uses the analogy of high-altitude flight and the United States Airforce’s 1940s missions to break the sound barrier.

“They believed that there were demons in the sky up there. And if you tried to break Mach 1, the demons would smash you to pieces – and they did, time and time again, test pilot after test pilot, but eventually Chuck Yeager got through and broke the sound barrier. And definitely in Antarctica, when you get up there near the pole there are some pretty intense feelings that there are kind of demons there because your brain is well gone in the very high altitude. You are basically starving to death. Your body shouldn’t really be at altitude for that long so you’re struggling a bit. Antarctica in my view is alive as a force – and a force that does not have any compassion.”

Drawing parallels between Antarctica and our behaviour is a big part of Swan’s polar work, which began after he made a promise to legendary oceanographer Jacques Cousteau in 1991, “To help protect the Antarctic Treaty”.

The Treaty, signed in 1959 and coming into effect in 1961, made the continent free from nation’s interests, free of resource exploitation and as an international shared hub for science and peace. It’s regarded as one of humankind’s greatest conservation achievements. However the Treaty is up for review in 21 years, and Swan’s “2041 Foundation” intends to make sure it is once again signed and upheld for another 50 years. However, protecting the continent from human exploitation on land is one thing, but protecting from human-made heatwaves and climate change is quite another.

“Antarctica does not have compassion. I believe it’s a force – possibly the most dangerous force on Earth because if we melt it, we all swim. It’s the most dangerous latent, powerful force on the planet. We all talk about Greenland melting. We talk about the Arctic melting, but it's got nothing if the Antarctic melts and sea level rises by 500 feet – then half the planet's finished.”

ORDINAY RITUAL, EXTRAORDINARY PAIN

In extreme environments, ordinary can quickly become extraordinary. One of the less-than-documented daily routines that Antarctic explorers must face on their heroic marches to the pole is the humbling, and ordinary daily tasks, like going to the loo. Imagine for a moment, trying to relieve yourself outside with no toilet, in minus-30 temperatures, your bare bum revealed to the icy winds in climatic conditions so fierce that skin exposed for more than a few seconds can be ravaged by frostbite.

“Obviously when you go to the loo in Antarctica, you are not sitting on a lavatory seat, you go outside, minus-30, you whip your trousers down and you squat over a hole that you have dug,” Swan said.

“I know it’s difficult to imagine, but I can’t tell you how hard it is to be careful when you are getting frostbite on your private parts, your fingers, your bum – everywhere – you just want to get it over with as fast as possible.”

Each morning, like clockwork, the team took turns in going to the loo before setting off on their day’s march.

On day seven Swan was first out of his tent for the morning ritual. He dug a hole, whipped down his trousers, bent over and in that instant, “Bang, like an electric shock shooting up my leg and into my hip. It felt like somebody pulled a wine cork out the bottle, but it was inside my hip. In agony, I leant to one side and it popped back in. All I could think, ‘oh shit’”.

Shaken, he carefully walked back to the tent and told his tent mate, Kyle, “I have a problem”.

The pair hatched a plan. No hip bends — at all. Swan would have to think through every tiny muscle movement of his hip, no matter how mundane the task for the rest of the march. This was a potential expedition-stopper for Swan less than a quarter of the way into the march. He had to be extra careful, “I knew I couldn’t get distracted by the cold and had to focus on what I was doing.”

Swan and the team pressed on. Days passed of utter exhaustion and seven-hours’ marching. Weary each night, Swan sent updates via sat phone to his following fans. And as the march wore on, he had no hip issues. Morning toilet trips went by undisturbed. At night-time in the tent, he felt pinches in his hip and struggled to sleep. After 15 days, the team had only 140 miles to go.

“It was truly a wonder to be with Johanna and Kathinka, the most powerful and kind women, and Kyle always rock solid in my life, the best of tent companions.”

Each day, Swan checked his mileage and distance and felt the urge to want to press on. “But I learnt real admiration for Johanna and Kathinka, who said, ‘no Rob’, no more, get in the tent and rest because we had made our daily average.”

100 miles to go.

“I was feeling really confident. The hip was good. And I was thinking, I’ve got this, I’ve just got to be careful, and I’ll be fine.”

Swan felt waves of euphoric joy unlike anything he ever had on his 200 days of polar marches of the past.

“I took it in, I looked up, away from the skis and the next step and allowed myself to enjoy it.”

At 87º South they hit a high plateau with howling winds and miles of sastrugi, parallel wave-like ridges, which are caused by winds on the snow’s surface, notoriously difficult and dangerous to ski along with deep gullies to fall into.

On previous expeditions, Swan and the team had only encountered about 20 miles of sastrugi, but nearly 70 miles of this treacherous terrain lay in front of them. Their progress slowed and the team were engulfed by a whiteout, a weather condition where visibility drops to zero - white sky, white cloud, white snow and no shadows or contours of any discernible element of the landscape or horizon can be seen. They were marching blind. “We had a few days where we couldn’t see anything in the white out, it’s like being inside a ping pong ball. You can’t see anything. You can't even see your skis. You can't see anybody in front of you and you're stuck in this sort of white world. And I realised if I fell over badly, I’m done for.”

Swan tried in vain to take pressure off his hip by pounding his ski-sticks into the snow in an attempt to stay upright.

“I was literally walking to the pole using my arms so I didn't fall over, which took everything I had, but at the same time, as painful as it was, I was starting to think in the back of my mind, I’ve got this.”

As the team ascended to nearly 9,000 feet above sea level, temperatures plummeted to minus-30 under deceptively clear blue skies and harsh 24-hour sunlight. After battling through the sastrugi plains the team emerged incident-free.

“Still, I felt nothing. No twitch, no electric-shock-loo-moments with the hip.” The next morning, Swan woke up in his tent next to his teammate Kyle.

“He said, Rob, you know every day for 29 days you've asked me how far we are away from 89º South. I don't know what's wrong with you, but you haven't asked me this morning, so let me tell you, we are 40 miles away from Barney and the Last Degree team”

He was almost there. Swan 33-year mission: 1,460 miles total, 40 to go.

40 MILES TO GO

On the morning of Day 29, Swan unzipped his tent and stepped out onto the ice desert of Antarctica. He looked around and peered into the nothingness. A familiar cold snap rattled him, and he recorded the temperature at minus-35 degrees. He knew as they continued to rise in altitude to the South Pole, it would only get colder from here on. As he walked away from camp, his mind raced with thoughts about how close they were to the pole. And how near he was to completing his goal. It was a matter of a few miles. He could almost touch the finish line.

“And so as I go to the loo, I am not thinking about taking my time. I am thinking about how close we are to the pole,” Swan recalled.Swan whipped down his trousers, squatted, and “Bang, the hip just came out of its socket and I looked down and the whole head of the hip, the metal head was pushing out my skin. Not piercing the skin, but out of the joint. It was unbelievable pain, like an electric shock that would not let go. Normally, you touch electricity and let go right away. But it wouldn’t stop. I was lying there unable to move.”

And so a mere 40 miles to the South Pole, Swan found himself in that moment paralysed on the ice in blinding pain unlike anything he had experienced before. Within seconds the minus-35 icy chill seeped into his exposed skin and sent uncontrollable shudders through him. As he lay gasping for breath in the snow, his eyes locked on something strange across the ice desert on the white horizon. “A figure in the distance coming closer”. All he could think, “Am I dying? This is it. The bloody Grim Reaper is coming for me,” Swan recalled.

“In my head I thought I was dying, and I could feel the cold seeping into my skin. As this electric shock feeling is going through me, I look up and I see a figure walking towards our camp. We are in the middle of a continent twice the size of Australia and there's no one else here, and all I can think is, fantastic, this is it. It’s the Grim Reaper coming to collect me and I'm dying. I thought maybe I'm having a heart attack with the pain. I thought, great, I'm dead because there is a figure that we did not expect to see. You don't suddenly see somebody in the middle of Antarctica. I shouted for Kyle and he came out, took one look at my hip, and said, Rob isn't looking too good.”

Kyle helped Swan make himself decent and dressed, and got his gloves back on. Johanna and Kathinka came out and helped carry their injured teammate back to the tent.

“Meanwhile, this guy who I thought was the Grim Reaper was actually a polar explorer from Poland who hadn't seen anybody for 49 days. He had been following our tracks and walked straight into our camp. Johanna asked him if he knew how to put a hip back in its socket. He shook his head and kept right on marching. We found out he made it to the pole a few weeks later.” The team bundled Swan into his tent and assessed the damage.

“I'm lying in the tent and I know it's over. Forty miles off after all that fight. Two times knocked back. And I think to myself immediately, if I get angry and frustrated, this isn’t going to work. Right then, I said to the team, ‘we will come back and finish this’. The second thing I thought, was give me more drugs for the pain.” The team radioed ALE (Antarctic Logistics Expeditions) for an air-vac. The same prop plane arrived that dropped them off 29 days earlier with a doctor onboard who Swan knew personally. Once again, Swan made the “depressingly short flight” to the South Pole. Upon arrival, Swan was stretchered off and loaded into a tent operated by ALE .

The hip simply had to go back in. As luck would have it two doctor friends of Swan, Dr Martin and Dr Hans happened to be at the South Pole base. And so, on the tent floor a few yards away from the South Pole, the two doctors administered pain medications, letting the drugs take effect, before pushing down on Swan’s out-of-socket hip in an effort to pop it back in.

“They had to stretch the muscles out and then, it just made a pop noise, one bang and back in. And I sort of woke up and asked for more drugs, and they said, ‘No, no’ Rob the hip is back in. You’re okay! Good guys,” Swan said. In the morning, still in pain, Swan asked ALE doctors if he could be flown back to his teammates to finish the 40 miles, but they quite rightly refused and instead he was flown out, with the worst moment to fly directly over his teammates.

“Simply awful, Swan recalls. “I wept tears of failure again.” “Kyle, Johanna and Kathinka would continue to 89º South to meet the Last Degree and then carry on to the South Pole.” Swan was flown back to the Union Glacier base camp where he met Barney and his Last Degree team who were preparing to fly to meet him at 89º South. It was a bitter disappointment as Swan senior watched his son’s team depart.

On the Last Degree team were Paulina Villalonga, a 19-year-old Student from UC Berkeley USA, Rob Miller, an entrepreneur from Chicago USA, Mary Nicholson, head of sustainability for Macquarie Bank, Ian Milbourn, an investor with Notion UK, John Foster, CEO of South West Gen USA, and USA war veteran Cameron Kerr, who had one leg, the other was lost in war.

Swan found out later that Kerr had travelled to Antarctica with none other than a little upturned bucket with a small loo seat on top.

“Had I taken one of those, we may be telling a very different story right now.”

Despite his personal disappointment, his son Barney stepped up and pulled off a successful march with the Last Degree team reaching the South Pole on January 13th 2020.

“That’s twice now he’s made it to the South Pole without his Dad. Pretty remarkable. And I think that's a huge message of hope for the younger generation and leadership on his part. That is a huge message for our survival on this planet. It has to be that we work together as generations because if we don't, we're screwed.”

Always the optimist, Swan is quick to point out the correlation between his own personal setback and the achievements of the other two teams, the Last Degree and remaining Last 300 team.

“It’s not all about Rob’s hip blowing out. This is something to learn in life, that when shit hits the fan in your own life, it’s important to keep the story going for others.”

A few days later, he arrived home to California on crutches.

“I was never disappointed until I got back home and I saw the piles of paperwork that it took me to make the expedition happen, all the boxes of equipment, and suddenly I thought, ‘My God, what an effort it took.’

OUT OF RETIREMENT — YET AGAIN

2021‘THE LAST 40’

You can guess what’s coming. In December 2021 Swan plans to return to the South Pole.

“All of us suffer injuries. All of us are told that we must do certain amounts of rehabilitation. And often we do it, but we don't do it for long enough. And I think that fundamentally I could have made the tissues and everything stronger so the hip couldn't have popped out as it did. I’m focused on making it stronger. I’m focused on saying I'll go in December, 2021 with Barney and we're going to knock it off and we're going to hope that Antarctica after smashing me back twice, will let me through to finish the job.” Swan’s walking tales now are intrinsically linked to his with 2041 Foundation and in support of Barney’s Climate Force Challenge.

“I think it's important when people say they are going to do something, they do it.” As a UN goodwill ambassador and climate change campaigner for the past 30 years, he has spearheaded hundreds of clean-ups, eco-sails around the world, education programmes, established education and clean energy hubs in countries worldwide. Young people, especially, are his audience and he challenges them through his 2041 Foundation to become sustainable business entrepreneurs.

“Every day, I ask people to do their bit for sustainability. I think it’s a good example if I do what I say I am going to do on my part.”

In 2021, Swan will be 65 when he plans his Last 40 with Barney and Paulina. “I’m still in the ring. I'm not going to give up. This may be the slowest walk across the continent of all time – 33 years, but I’m not in this for records. I’ve done that. This is personal and it’s to do what I said I am going to do.”

Swan plans to use his Last 40 to draw more attention to the plight of the polar regions and raise awareness for climate action worldwide.

“It's for me. And part of it is to close the circle on what I've spent my life doing. You know we all have dreams, and as you get into your 60s I think the message is don’t forget these dreams you had when you were a kid.”

One of Swan’s mantras for people who visit Antarctica is, “From now on, whenever you look at a map your eyes will go south to Antarctica”, and the same is true for him. In his study, he has a big map of the continent with lines drawn on it, scribbles of his expeditions. The 900 miles from the 1980s. The 300 in 2017. Now the 260 miles in 2019. He looked at the tiny space on the map – a matter of inches.

“I can’t leave it alone, with just 40 more to go, can I?

In a small way, I hope my walks might be inspirational to people to not let go of dreams. No one's ever walked to the South pole with an artificial hip. I'm sure people would say, ‘Rob, you've done enough. There's no need. You proved your point. We're not going to be truly inspired by you going to finish off 40 miles’. But you know, I'm not that sort of person. When I am lying in my bed as an old man I just want to think, sure, it was a bit of a struggle getting knocked back twice – but I finished the job.”

And if there was only one mile to go, would he still go back?

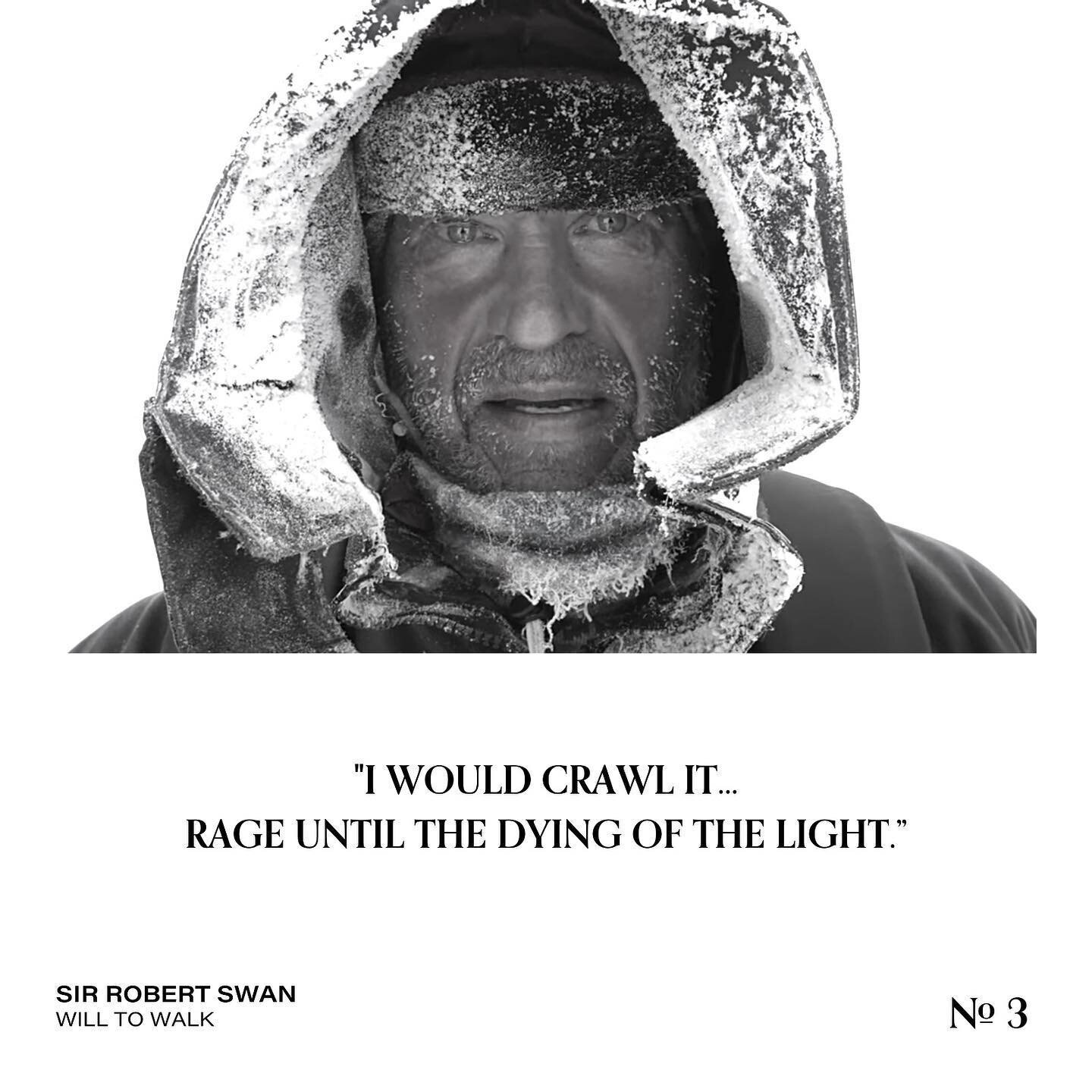

“Yeah, I would crawl it,” he said, “Rage until the dying of the light.”

All images copyright 2041 Foundation