#4 — DIARY OF A VOYAGE HOME TO A CHANGED WORLD

This is the diary of a voyage home to a changed world by Antarctic team leader, documentary photographer and former Sea Shepherd cameraman, Sam Edmonds. As the COVID-19 pandemic spread around the world, the Australian boarded one of the last tourist cruise ships to head south for the season. The Ocean Atlantic eased out from South America when there was a mere 2,000 cases of the virus worldwide, but returned with its crew and 200 passengers to humanity completely changed. In this episode, Edmonds reflects on his experience arriving back to civilisation from the seventh continent during a crisis, and the wider implications for Antarctic tourism post-pandemic.

Subscribe, share and if you like this episode, please rate it www.ratethispodcast.com/twopoles. Follow @two_poles (INST) @farfeatures (FB) www.farfeatures.com/twopoles & support https://www.patreon.com/farfeatures

Expedition team leader and documentary photographer Sam Edmonds recounts his journey to re-enter civilisation after being locked out at sea aboard Antarctic cruise ship The Ocean Atlantic.

Words by Fraser Morton

Photography by Sam Edmonds

On February 29, 2020, when Sam Edmonds was dropped off at Sydney Airport by his girlfriend, it was supposed to be a routine three-week trip to Antarctica. Little did he know, he was about to embark on a seven-week odyssey and return to a world completely changed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As he flew out to Santiago, Chile, and then onto Ushuaia, Argentina, the new virus COVID-19 was in its infancy with less than 2,000 cases worldwide and zero deaths in Australia. It would be two weeks before a pandemic was announced by The World Health Organization (WHO). By that time, Edmonds would be on a ship somewhere off the coast of Antarctica.

He was embarking on a voyage that he had made many times. For the past seven years, Edmonds has worked in polar regions’ tourism industry as a guide, photographer and team leader. Previously, he was a cameraman for Sea Shepherd, documenting anti-whaling missions in the Southern Ocean off Antarctica and illegal fishing operations in the Gulf of Guinea.

Despite being used to at-sea drama, this voyage would turn into one where Edmonds would experience an unprecedented series of events, hazards and biosecurity measures that today look set to have a lasting effect on Antarctic tourism operations for years to come.

“The last few weeks have proven one of the biggest professional challenges I have faced,” Edmonds said.

Tourists aboard The Ocean Atlantic in Antarctica.

BEST LAID PLANS

On March 2, 2020, Edmonds recalled it was a brilliant sunny day in the port town of Ushuaia, Argentina, the world’s southernmost town and jump-off point for Antarctic cruise ships departing to the seventh continent. This would be his last voyage South for the season. The long dark winter was approaching, a time when Antarctica enters icy hibernation and no ships make the treacherous Drake Passage crossing.

As team leader, Edmonds oversaw the boarding of the 200 passengers, who had travelled from 13 nations, with the vast majority of them hailing from Australia.

For many it would be the trip of a lifetime. One of the growing number of voyages that transport approximately 56,000 tourists to visit the continent each year aboard cruise ships like the The Ocean Atlantic.

The first week in March was the last week before everything changed for the Antarctic tourism industry. And The Ocean Atlantic was one of the last ships to leave before the pandemic escalated. The following week, a few more ships would depart south, including the now well-documented, Greg Mortimer.

At that point, Edmonds said that the only sign of anything out-of-the-ordinary was that the ship doctor was taking temperature checks of passengers as they boarded.

“As we set sail, I think most passengers felt positive about heading south and leaving this new COVID-19 virus behind them.”

The Ocean Atlantic enjoyed a remarkably smooth crossing of the infamous Drake Passage, the body of water ships cross to reach Antarctica between the tip of South America and the seventh continent.

“We had Drake Lake conditions, which were very smooth, very calm water — a great way to start the trip.”

Expedition crew await the arrival of zodiac boats filled with tourists at South Georgia, Antarctica.

King Penguin colony, South Georgia.

Landing at South Georgia.

The Ocean Atlantic arrived at its first destination, the South Shetland Islands, a remote archipelago about 70 miles north of the Antarctic Peninsula, where the team made a landing on a remote beach. While there is a human population at remote research bases on the islands, the group made no human contact with any outsiders.

Next, the ship made a short crossing to the Danger Islands, a historically famous location usually difficult to access.

“Up until this point, it was one of my best Antarctic trips. We got to see some up-close leopard seal predation of penguins and the conditions were on our side.”

But as The Ocean Atlantic made its way through Antarctic Sound, katabatic winds gusting up to 50 knots swept through the bay and the decision was made to cancel a landing and visit to Argentinian Science Research Base Esperanza.

“This was the first point where it emerged COVID-19 may disrupt plans. At that point one of our Chinese guests came up to me and asked if it was really the wind, or fear over a potential COVID-19 outbreak aboard the ship reaching the scientists. He very kindly offered for the Chinese guests not to go ashore and stay on the ship if those were indeed the fears.”

But Edmonds said the decision was made due to weather conditions. And the passengers never visited the science base or made any human contact.

“That is something I have reflected on a little bit due to the events that later unfolded.”

Tourists make a landing in Antarctica.

Tourists explore the Antarctic Peninsula.

Tourists aboard The Ocean Atlantic in Antarctica.

Antarctic Peninsula.

The ship stopped off at Point Wild, where passengers saw the famous bust of Captain Luis Pardo, marking the point where Ernest Shackleton’s Endurance expedition was rescued on August 30th, 1916.

“It was at this point that we received communication of the rapidly deteriorating situation because of COVID-19 happening back home.”

On March 17, now more than two weeks into the trip, The Ocean Atlantic arrived at Grytviken, formerly the largest whaling station on South Georgia, where they received word: “Entry denied”.

“We received communications saying we were being denied entry to prevent any risk of potential spread of COVD-19 to the scientists there at Grytviken. The ramifications of one of the scientists there contracting the virus would be pretty dire. This was now at the point that we felt that COVID-19 had reached us onboard.”

Unable to visit the science research base or the graveyard at Grytviken, The Ocean Atlantic crew and passengers were permitted to make a landing on a remote area with no human contact, at the king penguin colonies of St Andrews Bay and Gold Harbour.

“This wasn’t a typical voyage anymore. This was now something we were conducting within the context of a very serious global pandemic. We now realised it was something that was touching everyone on Earth, including our expedition ship in Antarctica.”

The cancellation of the South Georgia visit would be a small taste of what was to come, and the bizarre nature of the situation Edmonds and his crew now found themselves.

“We were in the comfort and security of our ship, experiencing wildlife, embracing the elements while learning new things daily. This was all while the world around us was facing a global crisis, with situations worsening politically and socially by the hour.”

Quarantined at Montevideo.

Tourists kill time while quarantined off the coast of Montevideo.

A sketch of The Ocean Atlantic’s itinerary onboard.

The Ocean Atlantic made a course for South America and after almost a full day of sailing for Puerto Madryn, Argentina, the health crisis had worsened and port authorities denied the ship’s request to dock into port.

By this time in mid-March, ports and borders all over South America shut down.

The Ocean Atlantic then made a course for Ushuaia. At the same time, onboard Sam and the rest of the crew were communicating with the Australian authorities as well as the ship management company and their health advisers as to how best to step up precautionary measures on board. Passengers and crew were quarantined to their rooms, with excursion times to the outside decks limited to two times per day. All public areas on board were closed and a three-metre social distancing rule enforced.

The ship was re-routed again the next day to Buenos Aires and at this time quarantine restrictions tightened and outside deck-time was banned. These efforts were made to try make sure further quarantine was not enforced by border forces when the ship was eventually allowed to dock.

The Ocean Atlantic was among a handful of ships also trying to regain entry back to the world, but remained locked out at sea. The varying ships quarantined at sea, would face different demands from border forces. Some ships were sentenced to a two-week quarantine onboard while in port, others were denied entry and ordered to sail back to their countries of origin, like the Netherlands or South Africa.

And a few ships headed for Uruguay, which took a more lenient stance on the cruise ship arrivals and promised a “sanitary corridor” for passengers to be repatriated.

With all ports inaccessible, the only option was Montevideo, where a “sanitary corridor” had been established. Upon arrival, there was another queue of expedition vessels already waiting.

One of those ships was the Greg Mortimer, a vessel that would become a big part of The Ocean Atlantic’s story, and a brand new custom-built ship with unique build specialised for cruising polar waters, what Edmonds describes as “an emblem of how great Antarctic tourism industry had been”.

Buses arrive to provide a “sanitary corridor” to Montevideo Airport.

On March 17, Edmonds looked at the sat-nav in the control room to see what other vessels were doing.

“Almost all of them had turned back to South America, but there was this one ship, Greg Mortimer, which was heading south to Antarctica. I remember the expedition leader and then looking at this interface and saying to him, ‘Do they know something we don’t’. We were curious as to their situation but they were 1,000 nautical miles away.”

In a matter of days, everything would change. Greg Mortimer changed course north and headed for Uruguay and within a couple of days would be within 13 nautical miles of The Ocean Atlantic. Communications were established between the two ships and plans were made to co-charter a plane to fly passengers to Australia and New Zealand, due to the lack of commercial flights available at that point.

“But 48-to-72 hours later, we heard of a handful of fever cases onboard the Greg Mortimer,” Edmonds said.

Test kits were flown to the ship and it was confirmed that there were a number of positive COVID-19 cases onboard.

“We had to cut all plans for an evacuation with the Greg Mortimer guests.”

It would transpire that 60 per cent of all passengers and crew aboard the Greg Mortimer would contract COVID-19.

The ship was eventually allowed to dock in Uruguay with a reported 128 confirmed cases of the virus onboard. The ship was carrying 217 people, the majority of them were eventually flown home mid-April, with many more still left behind and awaiting transfers.

Passengers leave after nearly a month aboard The Ocean Atlantic.

SANITORY CORRIDOR

Aboard The Ocean Atlantic, the crew and passengers had to bide their time, and so Edmonds turned to his photography to keep busy.

“Managing 200 people on an Antarctic expedition vessel amidst a global pandemic outbreak, it was important to maintain some daily rituals and de-stressors. For me, this was keeping my camera over my shoulder and focusing at times on the group of human beings on board our vessel.”

Eventually, The Ocean Atlantic was allowed to begin offloading passengers and within three days passengers from all continents other than Australasia would be offloaded.

For the remaining 140 Australian and New Zealand passengers, they were granted access to a sanitary corridor to the airport via buses and military guard. They arrived at an empty airport and their first sights of a world completely changed.

“It was a very bizarre experience to arrive at a deserted airport and as we moved through this process it just became surreal and hammered home the severity of this COVID-19 pandemic. Up until this point we had only been surrounded by the other passengers for more than a month.”

The charter flight flew from Montevideo to Santiago, Chile and the subdued socially-distanced direct flight to Sydney where the passengers were met by a proactive borer force.

They touched down in the early hours of April 3, 2020.

“While there was applause and elation to eventually be back home, as soon as we taxied and the door opened that joy quickly faded as we all made our way to our two-week hotel isolation.”

Exhausted crew and passengers en route to Montevideo Airport.

Sam and the rest of the passengers were put into hotel rooms for their 14-day quarantine. He spent his time taking photos and documenting the experience.

On April 16, 2020, at one minute past midnight, he was allowed to leave quarantine.

“It was almost miraculous we managed to get everyone back in the timeframe we did. Everyone got home safely and not one person from our vessel had COVID-19. Ultimately this seems like one of the steepest learning curves of my life generally, but especially in the Antarctic.”

Sam documented the whole trip, his essay, which appeared in The Guardian can be viewed here.

A subdued flight home to Sydney.

TOURISM IMPACTS

It’s too early to tell what the impact of COVID-19 will mean for the Antarctic tourism industry.

Some reports already suggest a 50 per cent cancellation for the 2020 Antarctic tourism season which is due to resume in October - with a resurgence expected in 2021.

High-profile cruise ship cases will not have helped ease travellers decision to book, with what Edmonds calls the “vilification of the tourism industry” due to COVID-19 outbreaks aboard the Ruby Princess and Greg Mortimer cruise ships that were widely documented in media reports.

Edmonds is optimistic about tourism’s return to Antarctica, and also its purpose in the first place.

One debate frequently raised regarding tourism to the seventh continent, is if it should be allowed at all.

“It’s a constant dialogue about how necessary tourism is to Antarctica, a place that is virtually untouched by human beings. Like any other wilderness area on Earth, we have a strong desire to preserve these places. However, putting big red tape around the entire continent to have it out of bounds might not be the solution to protect it. I see first-hand every day, what experiencing the Antarctic can do to someone for the rest of their life. I see tourism as part of the human condition. We all have a drive to want to experience things and see things. What else do we do with our time on this planet if we are not experiencing it as much as we can and celebrating this rock that we live on.”

View Sam Edmonds photography work at samedmondsstudio.com

Polar guide Sam Edmonds in Antarctica.

ARCHIVE INTERVIEW

(2018)

A POLAR GUIDE'S PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST GREAT WILDERNESS

Sam Edmonds is a polar photographer, guide and environmentalist.

I met Australian Sam Edmonds onboard the Ocean Endeavour in March 2018. I was there to film and photograph a documentary project for Eco-Business News with climate change activist group 2041, led by British adventurers Robert and Barney Swan.

Our first encounter was when he grabbed my arm to help me step from the ship to his zodiac, as we bobbed up and down in the Southern Ocean of Antarctica.

We got to chatting and sharing stories about work, and I quickly learnt that Sam has one of the best jobs in the world. He gets paid to go to Antarctica and the Arctic where he takes photographs of oceanscapes, wildlife and remote vistas. He has a unique insight into the polar regions that most people in the world don’t get to see.

Here, we discuss his passion for the polar regions and some issues currently facing the last great wilderness of Antarctica.

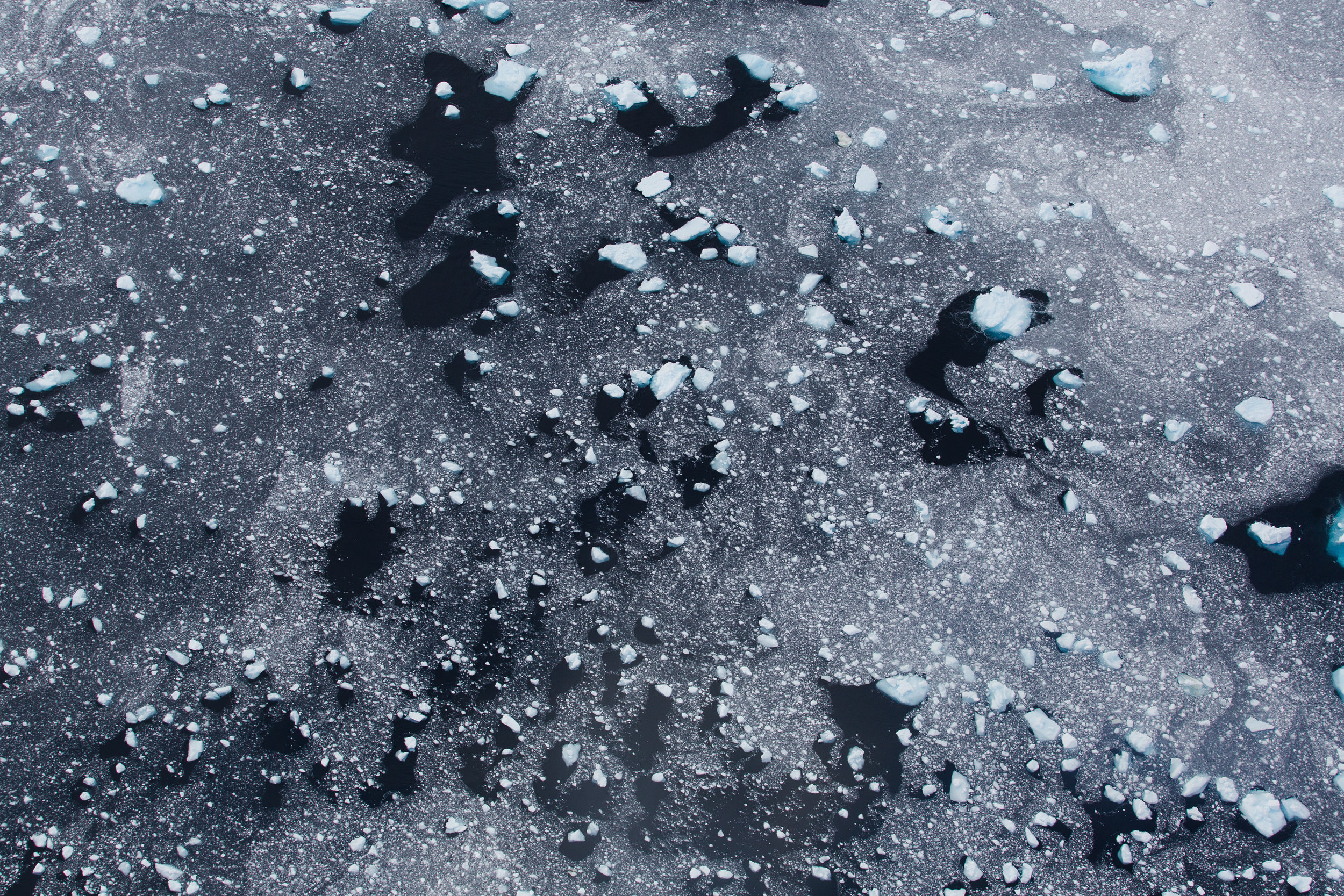

Antarctica from the air / Sam Edmonds.

FM/ How did you become a polar guide?

SE/ The idea of wilderness guiding in general seemed to make a lot of sense as a profession I would pursue as it rolls most of my skill sets into one. Also because it’s tethered to so many ideas about conservation and an almost Thoreauvian appreciation of the outdoors that I have advocated for most of my life.

How I got into guiding in a polar context really came about because I had managed to gain two seasons of experience in the Antarctic whilst filming the TV series “Whale Wars”.

ABOVE: SAM FILMED THE SERIES WHALE WARS FOR ANIMAL PLANET.

It was during that time that I obviously had the unique experience of learning about the continent first-hand, but upon reflection, was probably where I refined a lot of my “soft skills” as well: Working in a team under immense pressure, working in adverse conditions, building a rapport with people and generally being at sea for long periods of time.

FM/ What subjects are you drawn to photograph in the polar regions and why?

SE/ I often find myself in a sort of dual mode when I’m photographing in Antarctica. On the one hand, places like the Antarctic Peninsula and South Georgia afford an immense amount of wildlife photography to be undertaken, so I’m often working with that sort of visual language and in that stream of natural history documentation.

However, on the other hand, I’m also really fascinated by Antarctic tourism and how our collective perception of this ostensibly unexplored continent is being shaped by this unprecedented amount of average people that are seeing it with their own eyes for the first time.

So, most of the time I find myself switching between these two trains of thought and these two starkly different visuals languages as I explore both those themes as much as I can.

South Georgia, Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

FM/ What motivates you to keep going south to Antarctica?

SE/ I’m often asked this by guests onboard the ship, and especially when we have just come in from a very cold, wet and windy katabatibc experience somewhere! To be honest, I don’t really have an answer. I think that speaks volumes about these kind of subconscious answers that Antarctica provides for many of us as human beings.

I’ve asked almost every guest I’ve guided over the years, “Why did you come to Antarctica?”

There’s a startlingly wide spectrum of answers, but there always seems to be this theme of seeking the unknown and pushing one’s boundaries. It’s surprising how much a very cold and seemingly desolate place can seem to embrace you and offer solace.

Crabeater Seal, Paradise Harbour / Sam Edmonds

FM/ Most incredible thing you have witnessed in Antarctica?

SE/ That’s a really tough question to answer. Partly because I’ve witnessed a lot of moments of transcendence and camaraderie that were very astounding in their own right.

But most of those were as a result of immersing ourselves within the incredible Antarctic environment. However, there was one moment this most recent summer season (2017/2018) that seemed quite surreal and unprecedented.

It was in Antarctic Sound while we were transiting from East to West. A pod of killer whales was seemingly trying to isolate a fin whale calf from its parents, but at the same time a number of fur seals were swimming by and the usual suspects of sea birds were flying overhead in astounding numbers. I think we spent about four hours on the bow of ship just sprinting from port to starboard and back as all these animals surfaced and breached and frolicked right next to the boat.

I remember even some of the most experienced guides onboard were in disbelief at what they were seeing, let alone the guests who had never been to Antarctica before. So that was pretty special.

Fur Seal, Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

FM/ What worries you about Antarctica and threats to the ecosystem?

SE/ Like most places on Earth, even Antarctica hasn’t managed to escape the reach of our species as an array of threats are becoming increasingly ominous for this continent.

The impacts of anthropogenic climate change are being felt on the peninsula, but we are still yet to quantify the impacts of it locally. It will have detrimental effects on some aspects of the ecosystem but at the same time, some species like Gentoo penguins are thriving under the higher temperatures.

Personally, I’m very concerned by the exponential increase in krill fishing practices in Antarctica.

Russia, China and a number of other nations have openly expressed their intent to rely heavily on krill harvesting, which is incredibly scary. For anyone that has been to Antarctica, they have witnessed first-hand the importance of krill.

It’s the backbone of the entire ecosystem there and to exploit and tamper with that would be to pull the rug out from underneath the entire ecosystem. This needs to be addressed immediately and we will have to take a long hard look in the mirror as a species if we decide that that is a gamble we are willing to take.

Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

FM/ How do you describe Antarctica to people who have never been?

SE/ I often tell people that if they have ever wondered what the planet was like before Homosapiens, you can catch a glimpse of it in Antarctica. In many ways, I think that’s what makes this place so special. It is the world’s last remaining wilderness.

FM/ I feel like the photos I took down in Antarctica don’t do it justice one bit. Can a photograph capture the essence of Antarctica?

SE/ I’m not convinced that an image can capture the essence of anything. Photojournalism is going through some rather tough growing pains at the moment as it grapples with tearing down that precarious, false sense of “objectivity” that it advocated for so long.

And I think this is really healthy. Especially in an age where we consume to many images, yet so little of us are consciously visually literate. What I do think visual media can do for us and what applies to the polar regions is the collective voice of visual documentation that can start to shape a better understanding.

All visual crafts are inherently subjective, but as a chorus of viewpoints starts to harmonize, the power of bearing witness increases exponentially. This is when we see movements begin and things start to change.

FM/ Do you have a favourite quote you’ve read about Antarctica?

SE/

“The first great thing is to find yourself and for that you need solitude and contemplation - at least sometimes. I can tell you deliverance will not come from the rushing noisy centers of civilisation. It will come from the lonely places.”

- Nansen

---

If you like Sam's work and want to buy one of his prints,

visit samedmondsguide.com/print-store

Far Features supports independent artists we respect.

Antarctica / Sam Edmonds

If you like this story please see more of our latest Far Originals projects and support independent creative non-fiction work at www.patreon.com