KONYAK : TIME WAITS FOR NO WARRIOR

FEATURE Nº 21

The last generation of Konyak warriors, Lungwa village, Nagaland. Images: Justin Ong

A film by Sadiq Mansor

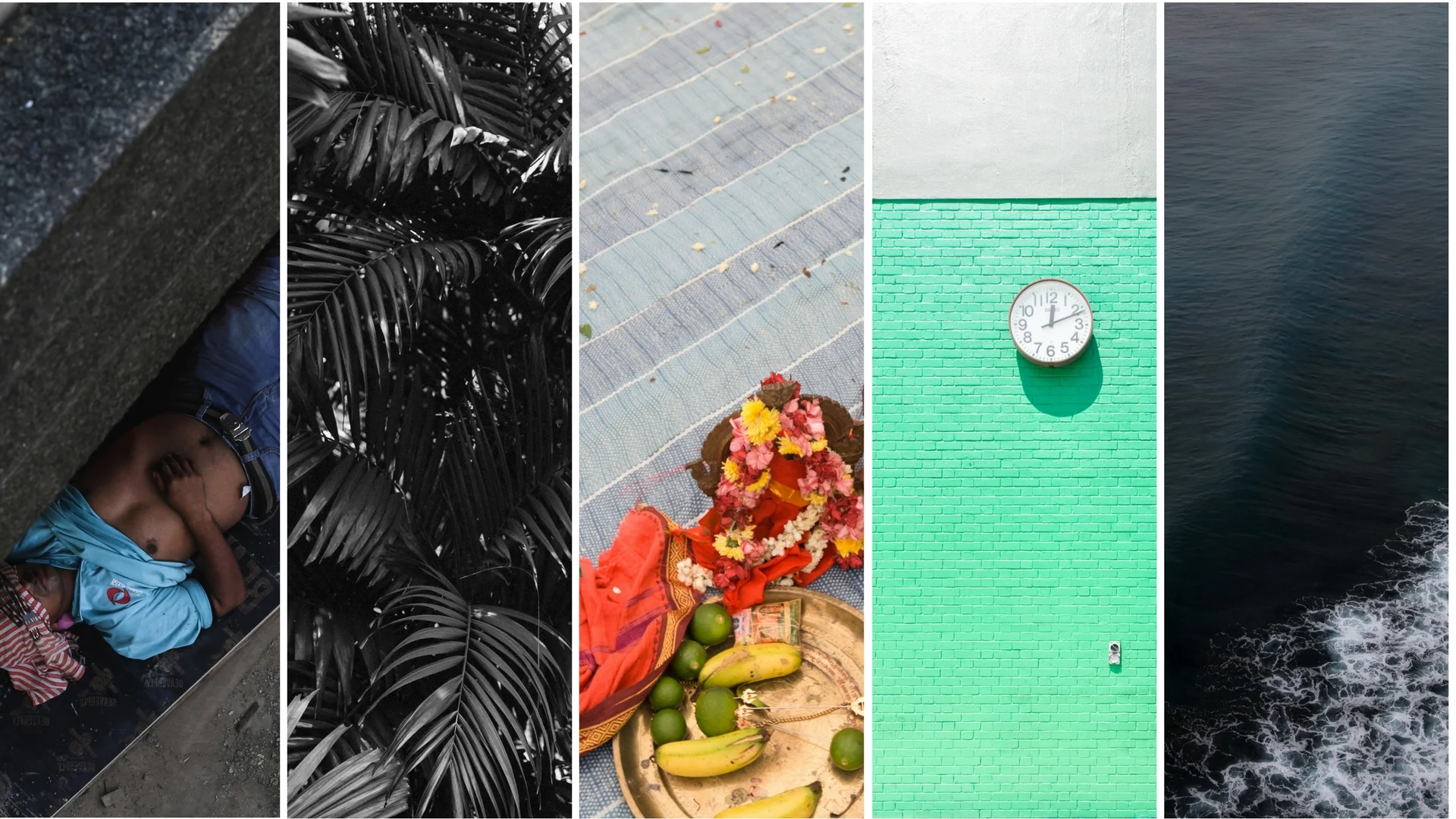

In the misty borderlands between India and Myanmar, The Konyak warriors are vanishing into the chronicles of history in this remote region of the world.

The Konyak are members of the Naga people who have lived in the verdant northern Indian state of Nagaland for hundreds of years, observing ancient rituals passed down through the generations.

They are most well-known and documented for their warrior headhunting practices, which for hundreds of years formed the spine of the tribe’s status, order and hierarchy.

In the past, the Konyak observed animism and worshipped all elements of the natural world, including plants, trees and natural phenomena, believing the living world itself to be a spiritual being.

Among the Konyak culture, honour has always been integral to tribal customs. Fierce battles and raids of neighbouring hillside and forested villages would end with victorious Konyak warriors returning home with enemies’ heads. In return, they would receive their reward of fresh ink and new tattoos on their face, neck, arms, legs and back. These symbols on the skin represented the warrior’s place within the tribe, their many battles and life’s journey.

At the turn of the 20th Century, worlds collided when Christian missionaries made contact with Konyak, spreading new ideas, ideologies and religion throughout the land.

Initial resistance soon turned to acceptance. Slowly, Christianity ebbed into daily life. Divinity changed. Gods changed. Buildings changed. Roofs grew spires and crosses looked down upon the Konyak land.

Like so many other indigenous populations around the world, soon Christianity was accepted as the new faith. Little did the tribe realise, this would spell the end for their long history of rituals.

Under British rule in 1935 headhunting was outlawed. While some continued under the radar, by the 1970s the practise had faded into the history books.

Today, almost all of the Konyak communities in the region known as Nagaland have converted to Christianity. Most villages have a church and Sunday services presided over by a pastor.

The elderly warriors’ tattoos fade with age and headhunting exists only in the words of recounted tales to the younger generations, anthropologists, filmmakers and journalists. There are also worn reminders in necklaces adorned with little bronze heads, which symbolise how many enemy skulls a Konyak warrior has collected. One means one, but two, three, four, five or more can mean many more real human heads.

The warriors’ children and now grandchildren wear modern clothes and go to church on Sundays. They cram into the small white chapel and sit elbow-to-elbow smartly dressed. They sing hymns. They pray. They smoke. They listen to the pastor's preaching from bibles. Sometimes the old warriors wander inside, too. Their heavily tattooed faces cut a sharp contrast to their pristine white collared shirts, like two different generations sitting in one pew, one body.

The Konyak story is a familiar one of worlds colliding. Where tribes and ancient rituals meet the modern world and generations pull away from remote roots to enter the human centres of civilisation, enticed by money and new religions.

These last remaining Konyak warriors are living time capsules to the past, whose stories chronicle tribal times fast-fading from the eyes of the world.

Words by Sadiq Mansor & Fraser Morton

Nagaland, northern India. Images: Justin Ong