FINAL ACT OF THE STILT FISHERMEN

FEATURE Nº7

THE LAST MEN BEHIND SRI LANKA's ICONIC IMAGE

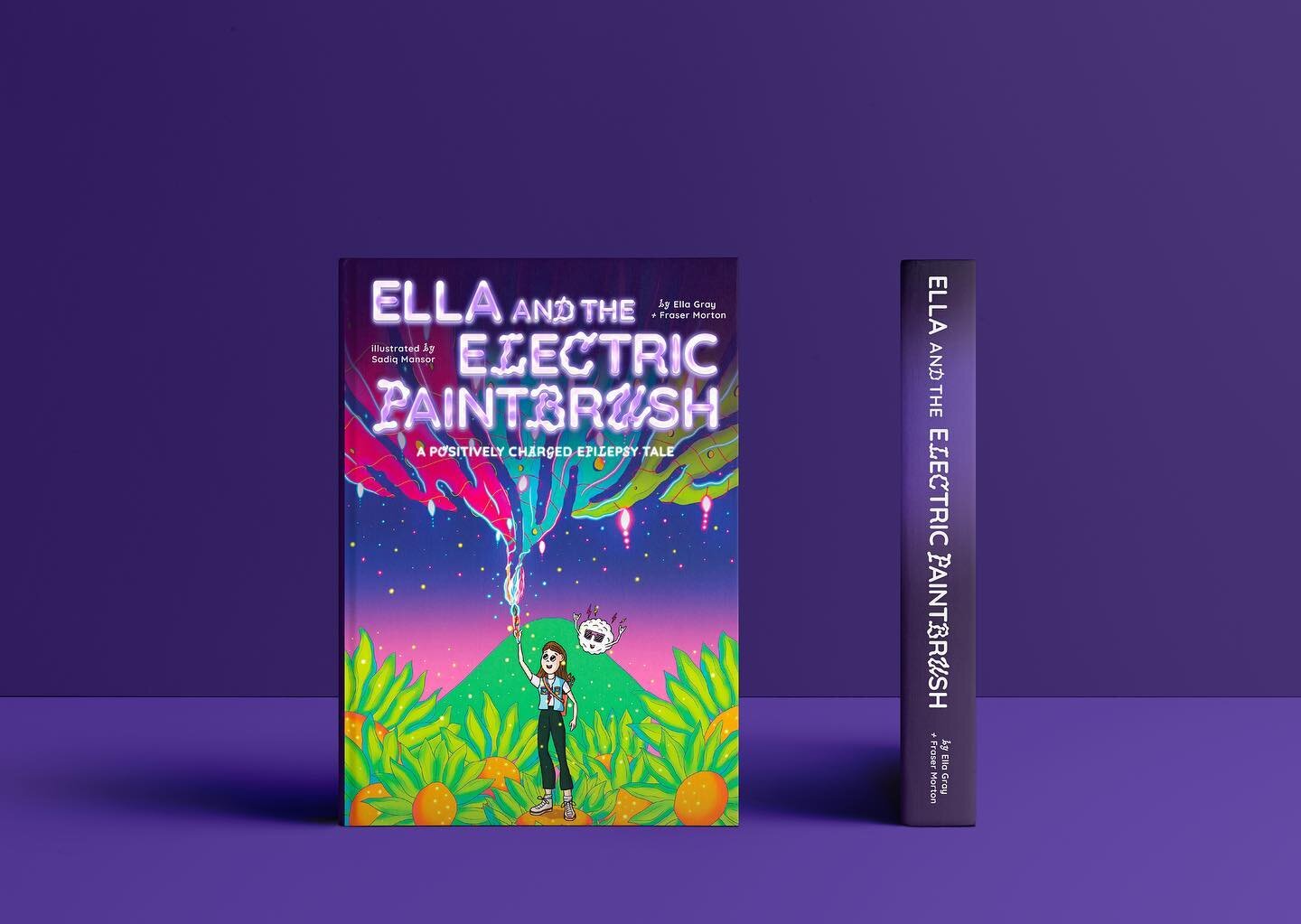

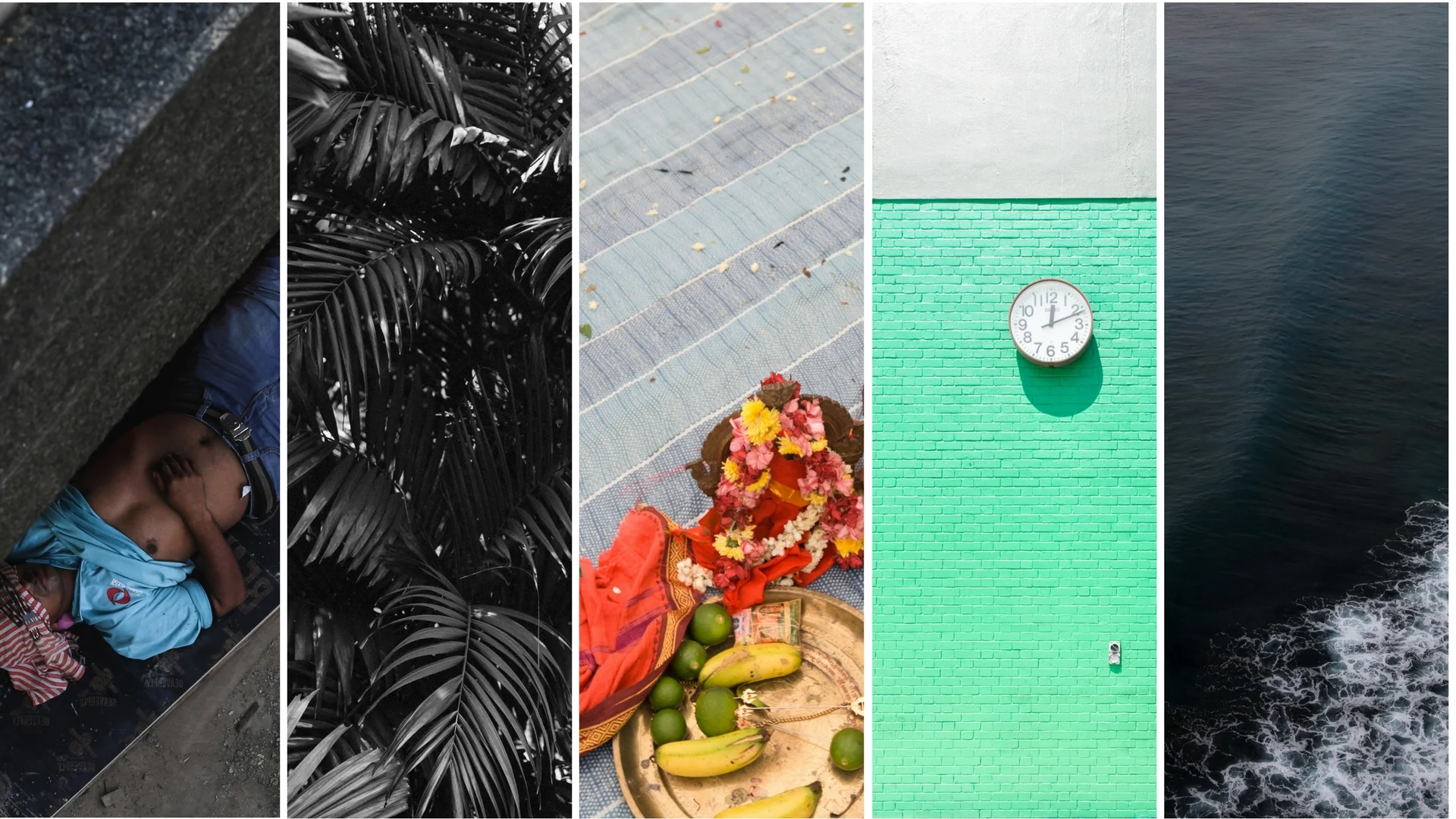

Two of Sri Lanka’s last stilt fishermen. Photo by Fraser Morton 2017

A man fishes from a wooden crucifix a few metres above crashing waves that fizzle out on the shoreline. The scene could be a hundred years ago. On his head he wears a turban. No shirt or shoes, only a ragged sarong. He looks a picture of tradition, a spitting image of the men who coined the style of fishing after World War II.

Despite the appearance there are no fish being caught. A few rupees from tourists are the only thing being reeled in. The tradition of stilt fishing is no more. Except, maybe, for Samaat and his friend.

He's not easy to find. But a few kilometres along the coast from Mirissa at Weligama we find him on his fishing perch. He is not a picture of tradition. He wears sports shorts and a rash guard, a gift from his son who runs a local surf school. Samaat says that he and his friend are the last men in the area who still use the style of fishing.

"Each night I go out. I go to my perch (petta). My one is that one over there," he says pointing to the farthest wooden crucifix, about five metres out to sea.

"We fish like this for fun," he says, smiling. "To relax. Why else would anyone fish this way these days?"

A fishermen poses for tourist photos.

The style of fishing is crude and inefficient. It was originally coined following World War II, when limited food and fishing areas prompted some men to innovate. Today, however, while many of the pettas remain rooted in the sand, the fishermen have gone to sea. Entering the more lucrative deep-sea fishing industry, or working on whale watching tours.

It was American photographer Steve McCurry who brought the stilt fishermen to the world's attention with his 1995 series, creating iconic images that travellers to this day come in search of.

Samaat says it's only a matter of time until the tradition dies out.

"It's a bad way to fish," he says. "It hurts your bum and back and you catch very little fish."

Samaat, one of Sri Lanka's last stilt fishermen.

Samaat is indifferent to the fishermen who pose for tourists. He says times have been tough and that tourism brings in more money.

"I don't care if that's what they do," he says laughing. "Every man must do what they can for their family."

Samaat lives a stone's throw from the spot where he fishes, across a busy highway that lines the coast. His house was donated to him by the government after his last one, and the surrounding coastal area of Weligama, was devastated by the Asian Tsunami in 2004. More than 2,200 homes were washed away and 469 people perished. He and his family also survived the most recent floods that left scores dead and displaced half a million people in May, 2016. Tough times never seem far here.

Samaat doesn't catch many fish. Enough for dinner most evenings, but he says he will keep stilt fishing for as long as his bum and back allow him to.

"It's not a bad place," he says, looking out to sea as the sun blazes over the horizon.

By Fraser Morton & Eszter Papp

Samaat and his friend fishing at sunset at Weligama.