THE MAN WHO SLEEPS IN A VOLCANO

FEATURE Nº6

THE LIFE LESS ORDINARY OF AN INDONESIAN MINER WHO SLEEPS WITH A VOLCANO GOD

By Fraser Morton

Let’s say that every day you walk to work carrying two men on your back. On the way you hike up a mountain prone to landslides and toxic wildfires. You pass tourists who take photos of your torment. When you arrive at the office your boss hands you US$10 for your efforts. He says go back and bring me two more men tomorrow. You agree because if you don’t your family will starve. Beaten and weary that night you sleep at the office. God sleeps there, too, in the next room over. In the middle of the night the office explodes in a toxic inferno. You survive knowing god was angry that night. This is Monday. Tuesday will hopefully be better.

Almost anywhere in the world, this job would be labelled insane. But for sulfur miner Arifin, who works and sleeps in the highly active volcano Kawah Ijen, it’s simply part of the job.

Arifin, 47, has spent all 26 years of his adult life here. He followed in his father’s footsteps. He’s seen many of his friends die over the years. More than 70 miners have perished since the mine opened in 1968. Killed by landslides, eruptions, inhaling toxic gas, being crushed by rocks, falling over cliffs or losing battles with chronic lung diseases. There are many ways nature finds to kill these men. So Ari and the other 300 miners ask a giant Hindu volcano god to protect them. They believe she dwells in the acid crater lake. They say when she gets angry, the volcano erupts.

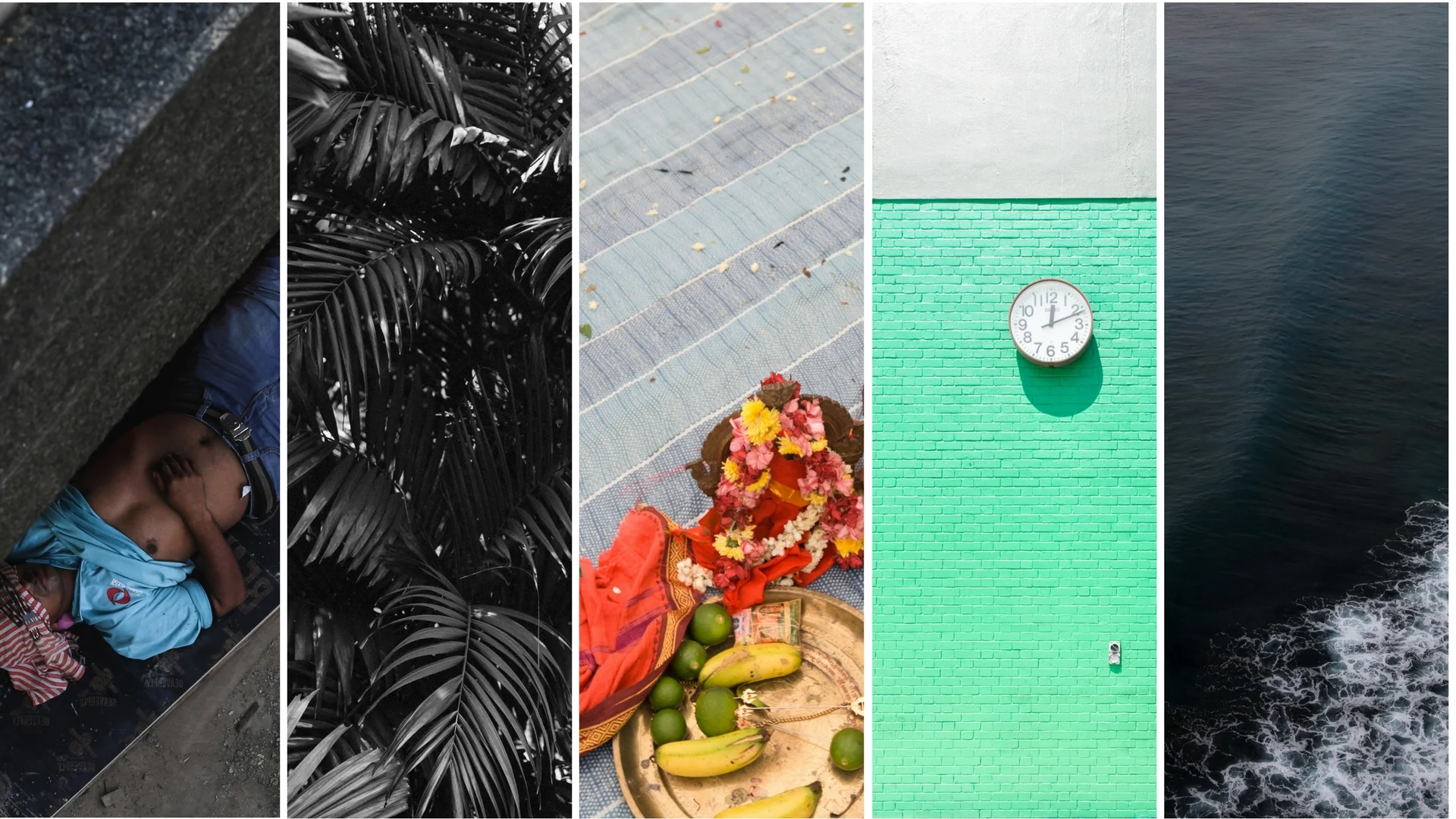

Sulfur miner Arifin inside Kawah Ijen volcano crater.

Sleeping With God

“In this place we can say there is someone or something who is looking after Kawah Ijen. Like the spirit who lives in the lake, she’s called Mbah Ijen. We call her Grandma,” Ari says.

It’s little after midnight and Ari is in his makeshift tent, sandwiched between the mine and the crater lake. He sits on his bed made from logs with an old blanket for comfort. In one hand he holds a flame torch, the other a lit cigarette.

Ari says Grandma hears everything from the depths of the crater, as he nods outside the tent. In the pitch black the world’s largest lake of acid seethes yards away. It is the kilometre-wide, 200-meter deep turquoise jewel of Kawah Ijen, but Ari and the other miners wouldn’t dare swim here. Not if they want to keep their clothes and skin.

Ari and the miners are all Muslim, but they worship Grandma as a Hindu mountain god who predates their own religion in this region of Java. These devout men of the mountain even have a volcano Imam, who every December leads a procession of miners into the crater. He slits a goat’s throat and tosses it into the lake for Grandma to feast on. A sacrifice of honor across religions.

A miner organises his sulfur just after dawn in the crater of Kawah Ijen.

Grandma has shown herself in many forms over the years. “Like this one time I saw footsteps. They were about two-to-three metres long,” Ari says, taking another long drag of his cigarette. Other times he wakes to the sound of children laughing and hitting drum barrels in the crater. Grandma likes to play tricks on him.

A few months ago, Ari was stirred awake by water splashing on his face and the sound of thunder. Stumbling outside his tent he looked skyward as a 25-meter geyser of acid water shot up from the heart of the lake and rained down onto his ramshackle tent. “I ran as fast as I could and climbed out of the crater,” he says.

Ari could speak all night about his narrow misses with Grandma’s anger. He’s been spared so far where others have been sacrificed.

Every two weeks Ari leaves Grandma, the sulfur mine and the crater to retreat down the volcano to the sanctuary of his other home - the remote village of Licin on the outskirts of Banuwangi, where the majority of the miners call home. For Ari, it’s a two week rest during which he can see his family, farm his friend’s rice field, enjoy showers, attend mosque and pray to his other god. But not tonight. Tonight he’s here with Grandma. He has work to do.

Arifin takes a cigarette break on his way out of the crater. The miners all smoke heavily.

Dare To Die

It’s 2am and Arifin makes the short walk to the mine, his torch flame slicing through the blackness a few feet in front of him.

“We miners have our own saying we live by,” he says, arriving at the foot of three giant pipes, billowing white smoke into the night. “Dare to die, afraid to starve. Better I have a tough a job than my family starve.”

Living with death so close has forged an unbreakable brotherhood between these men. As one of the head miners, Ari is seen as a father figure by the younger ones.

His job is one of the most crucial at Kawah Ijen, one that also means he must sleep in the crater to ensure it’s safe for the other miners. He maintains the mass expanse of cooling pipes that funnel the hot liquid sulfur down into the belly of the mine.

Shouts and whistles echo down the crater walls. The other miners, who sleep in a hut halfway down the volcano, have arrived at the crater rim, 800 metres above. Arifin whistles back and sets to work, disappearing into a cloud of toxic gas, the sound of his pickaxe clanging on hardened sulfur. Minutes later he emerges coughing uncontrollably and carrying his wicker basket on his shoulders laden with yellow sulfur.

Ari stands just five-and-a-half feet tall (168 cm) but has strength that perplexes the average person. As one of the strongest miners he can carry up to 130 kilograms of sulfur on his back straight out of the crater and three kilometres to the nearest weighing station. He’s rewarded with US$10 each day, if he carries a minimum of 90 kilograms of sulfur on his shoulders. It’s the highest paid job Ari can hope to earn in the region.

Arifin is also the mine's communications officer. He calls a Java radio station each day to let them know the conditions at Ijen for tourists.

The miners now rely on a few extra rupiah posing for tourists' photographs.

Toxic tourism

“Kawah Ijen is an exotic place for visitors, but for us it’s like hell,” Ari says.

It’s 3am and, as Ari and the other miners work, high above them a trail of tiny shimmering torchlights zigzag down the crater wall. Tourists, in their hundreds, are on their way down them.

Tourism to the mine really began in 2002, when a strange phenomenon started at Kawah Ijen. Blue fire began to burn in the crater. An anomaly caused by a combustion of sulfur gases sending blue flames up to five metres into the night. Tourism quickly ignited, too. First domestic, then foreign. Then in 2011 another foreign anomaly descended on the volcano: film crews. National Geographic, The BBC, and Al Jazeera have all filmed documentaries here, bringing Kawah Ijen into living rooms around the world. One US travel show host even paddled a dinghy out onto the crater lake to see if it would sink. The curiosity of armchair tourists was well and truly piqued.

READ THE REST OF THIS FEATURE HERE

The miners carry up to 130 kilograms of sulfur on their backs out of the crater.

STRENGTH & SCARS

This last photo is my favourite because it shows Arifin as I came to known him. A strong, proud and happy man accepting an outsider into his home. I spent a lot of time with him and his family and what I learnt is that he's a man of great dignity and pride. Like all the miners, they have a tremendous strength of character. They seem unbreakable, even from self-inflicted hazards like chain-smoking. Their strength and scars are results of years of work mining for devil's gold. The "why?" is the question that most people want to know. Why do these proud men do this job. Well, that's an easy one: money. It's the best paying job and there's a market demand. The sulfur Arifin burns his hands to mine each night and breaks his back to carry out a volcano is so we can wash our hair and make our skin nice and soft. Arifin and the other miners remind me that the things we buy are always at the expense of someone.

---

As I watch the miners work for the last time, I imagine their song being carried on a toxic breeze out of the crater and into the ears of the tourists hiking the volcano, travelling across this volcanic archipelago nation to Jakarta, Singapore and Hong Kong, where it catches the attention of shoppers standing with baskets of shampoo, skin-cream and sugar laced with sulfur. Their song should strike a chord that luxury is a burden carried on the shoulders of some very strong, honourable men.